by Michelle Waycott

Last Sunday (9 April), at the opening of an exhibition of Jennifer Keeler-Milne sketches, ‘Drawn to a cabinet of curiosities’ at the Museum of Economic Botany, Adelaide Botanic Gardens, I was asked to explore the importance of how art and science may work together. After the event a few people asked me to share my discussion with them…

Curiosities brochure cover

Before I get into that, if you are in Adelaide or passing through, let me encourage you to consider visiting this exhibit. The drawings are an evocative collection of works, based on objects in nature which the artist, Jennifer, tells us she put together over a period of at least three years. They are created in a style which an observer described as being ‘sculpture-like’ because the artist must visualise the final artwork where the pieces of paper she wishes need to remain untouched, the remainder being filled in with charcoal leaving a white image on a black background. This must be a technically challenging approach to create the images of sometimes very delicate structures such as her depictions of feathers, urchins and plants. Highly creative, these pieces are intriguing and together make a collection of interesting ‘objects’.

Creativity is certainly fundamental to the human existence and we often underestimate its importance in and on our lives. In addition, the interaction and interchange of science and art allows exploration of new boundaries through what are essentially creative processes. As a result we may see expansion of our horizons of understanding along with new understanding and expression in our lives—both professional and personal.

Both art and science require a nuanced appreciation of the focus of the works. Both artists and scientists explore details, which they then try to synthesise to reduce or depict complexity and to then communicate their insights to their audiences. Their creative processes generate something from nothing—more from less—understanding from chaos.

The intersection of art and science might be viewed in many ways:

- art for science

- art about science

- art from science

- science in art

- science for art

- or even science–art or art–science…

- but in my view, and critically, art with science and science with art.

Word games aside these two disciplines have complex interactions. The modern expression of art in its various forms—literature, performing and visual—have become inextricably tied to scientific and technical developments, and conversely, scientific advances have come from insights gained through art.

We cannot deny the beauty of artistic representations of the Fibonacci sequence nor how elemental photography provides us with new views and insight of our world.

Indeed as a botanist, and in particular as a taxonomist, a fundamental tool we use for our work is botanical art which captures the essential features of a plant, depicting the features essential to describe a species so that others may understand the work we have done and the concepts we wish to share.

Both science and art have been enhanced at their interface—through the growth in scientific understanding of the universe and new technologies in everything from new types and colours of paints to musical instruments, writing and computers, digital sharing of works, new types of papers and storage techniques. Today works or pieces of art can be essentially immortal—or transient—simultaneously, depending on their medium and methods of sharing.

But back to the exhibition here… What insights do we gain from art and science together?

The artist, Jennifer at curiosities launch

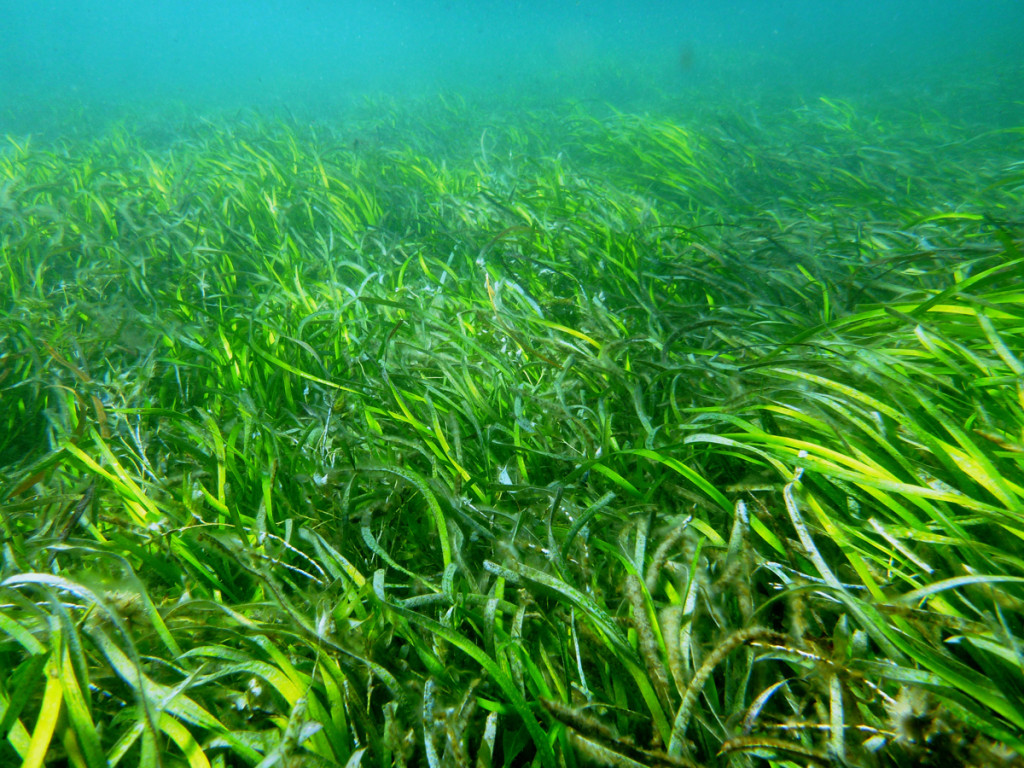

As a scientist, I can’t help but try to create order, insight and understanding that come from reviewing Jennifer’s collection. In agreement with the inspiration for the exhibition, the concept of a cabinet of curiosities comes across in the sense of special, wonderful, unusual and uncommonly combined objects that are drawn and placed together with the addition of Jennifer using the difficult, and very particular, technique in their creation. Her ‘cabinet’ contains wonders of diverse origins, as she describes them—land, air and sea. The pieces have been put together in with an artistic approach to taxonomic groups. Rocks together in a collection cataloguing their diversity, the varied forms of corals, a staged collection of moths, feathers from different birds and the various feather forms…

However this collection has not had a scientist ‘walking’ alongside the artist informing them of the detail. The Acropora, Pocillopora, Porites, Fungia or Lobophyllia could be rocks, butterflies, plants or corals…

Curiosities drawings of coral

Rather than being a limitation, I think, this gives the viewer the perspective to allow them to interpret the works in their own way—without the names we are left to wonder what they are—like the original cabinets of curiosities they are gems of like grouped objects that are intrinsically wonderful and curious in their way.

This also means that when science does provide other insights that come from a different type of understanding the collection can take on a new dimension. By knowing, for example, that Porites is a coral and that it forms massive, sometimes ancient aged individuals that are the basis of many reefs around the world, we can enjoy the wonder of an expanding and new experience that comes from the knowledge. Then move forward, open another chapter in the story that comes from accumulated creativity and new work and then ask ourselves—what next?

This exhibition is open until the 9 of July, 2017.

This week, some 150 delegates from around the world converged on Panama City to discuss the

This week, some 150 delegates from around the world converged on Panama City to discuss the

You must be logged in to post a comment.