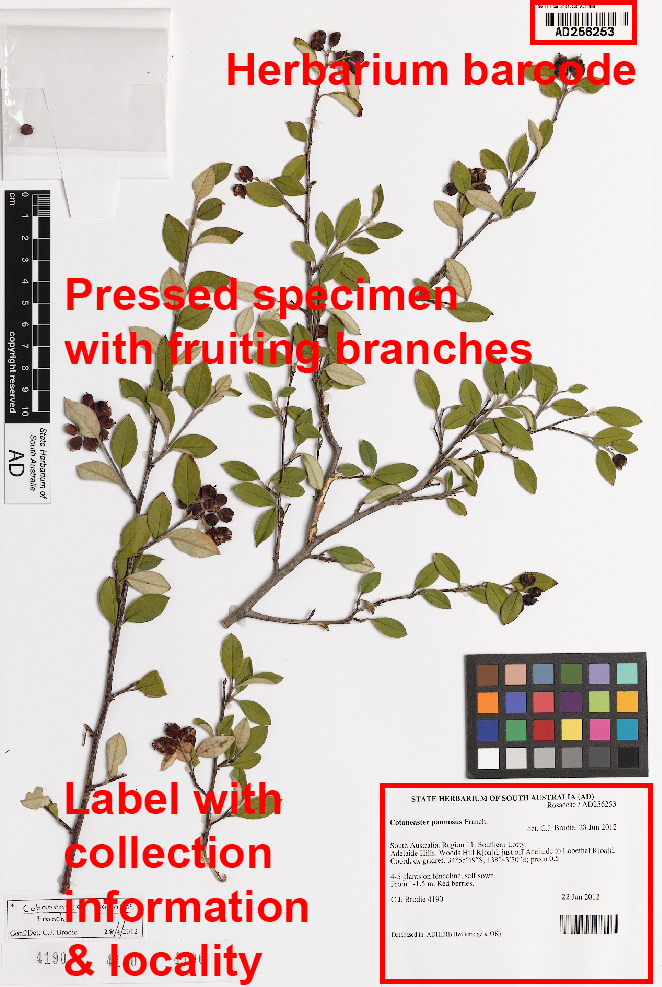

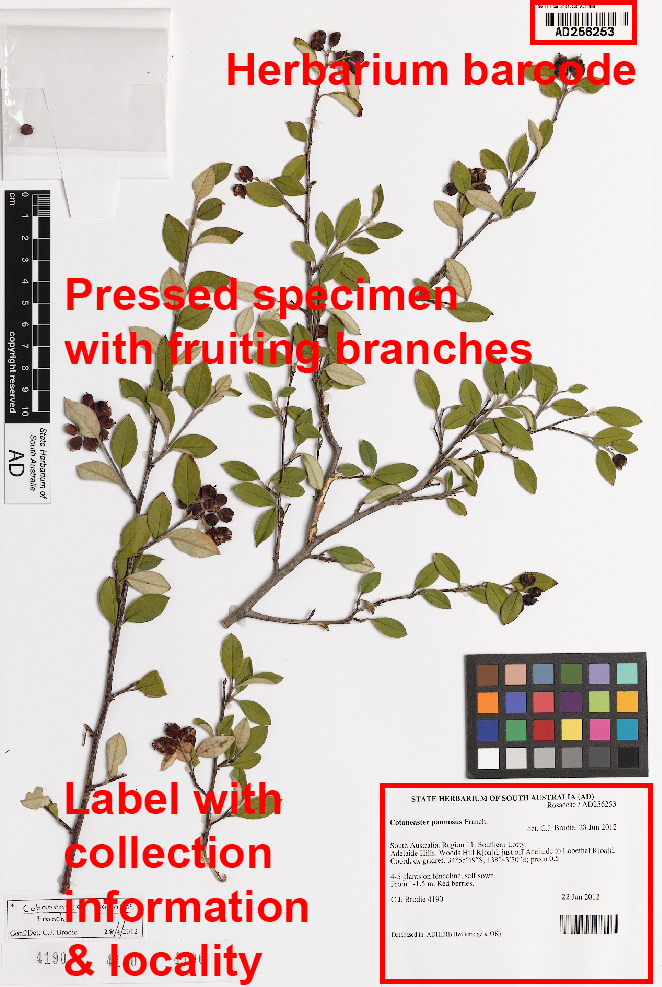

Herbarium specimen of Cotoneaster pannosus, consisting of stems with leaves and fruits, label with collection information, and a barcode that identifies the sheet.

The State Herbarium of South Australia documents and lists all known plant species that grow wild in South Australia. We are able to do this for both introduced and native species, with all observations verified by voucher specimens. These are stored as permanent verifiable records of what species grew where and at which time.

Herbarium specimens have two main components: The actual specimen is normally a pressed and dried plant, or part(s) thereof, that can be used for identification. The second part of the specimen is the data associated with the collection. This includes, but is not limited to, location, frequency, habitat, habit and any other obvious observations. This data are as important as the preserved plant itself. Having one part without the other renders the specimens almost useless.

State Herbarium Weeds Botanist, Chris Brodie is responsible for identifying and cataloguing the wild non-native plants for South Australia. Especially important are any previously unrecorded wild populations of non-native plant species that are new to the State or new to individual regions, especially those in the early stages of establishment that could be the next ”big problem weed species”.

Cardiospermum grandiflorum (Balloon Vine), a species listed as naturalised in 2017. Photo: C.J.Brodie.

Weed species are organisms that adversely impact natural and agricultural environments. Some known problematic weed species in South Australia are:

The Weed Management Society of South Australia (WMSSA) provides a forum to share knowledge, debate issues and generate ideas, drawing on practical weed control experience and the latest research. New members are always welcomed and events are open to all. The Society brings together people actively involved in managing weeds and researchers with interests in protecting our agricultural and natural environments. The main aim of the WMSSA is to minimize the “impacts of weeds in South Australia, on our economy, environment and society”.

At this year’s Annual General Meeting of WMSSA, Chris Brodie was voted in as Secretary of the Society. This is a great opportunity for the Herbarium to involve itself in the wider weeds community in South Australia, and it is with enthusiasm that Chris assumes this role in the Society.

At this year’s Annual General Meeting of WMSSA, Chris Brodie was voted in as Secretary of the Society. This is a great opportunity for the Herbarium to involve itself in the wider weeds community in South Australia, and it is with enthusiasm that Chris assumes this role in the Society.

Next year, the WMSSA will be holding its 6th bi-annual conference on 2–3 May 2018 at the Waite Plant Research Centre. Further details can be obtained from the June edition of Weedwise, the Society’s newsletter. All are encouraged to get involved and interested parties should keep their diaries clear for the 6th WMSSA conference in May.

Contributed by State Herbarium Weeds Botanist Chris Brodie.

At this year’s Annual General Meeting of WMSSA, Chris Brodie was voted in as Secretary of the Society. This is a great opportunity for the Herbarium to involve itself in the wider weeds community in South Australia, and it is with enthusiasm that Chris assumes this role in the Society.

At this year’s Annual General Meeting of WMSSA, Chris Brodie was voted in as Secretary of the Society. This is a great opportunity for the Herbarium to involve itself in the wider weeds community in South Australia, and it is with enthusiasm that Chris assumes this role in the Society.

You must be logged in to post a comment.