Protea cynaroides, a newly recognised weed, originally from South Africa. Re-generating parent plant on Kangaroo Island. Photo: C.J. Brodie.

The State Herbarium of South Australia documents all known plant taxa (species, sub-species, varieties and forms) native and naturalised (weedy) in South Australia. These are listed in the Census of South Australian Plants, Algae and Fungi. All newly discovered State and regional records are added to the Census throughout the year. These records are based on preserved plant specimens, verified by a botanists and housed in the vaults of the State Herbarium.

For all new records of non-native plants, an annual report is produced by Weeds Botanist Chris Brodie and Senior Botanist Peter Lang, both from the State Herbarium. The report includes the list of new weeds recorded for South Australia with locations, descriptions and photographs. Also documented are updates to taxa that have had a change in distribution, weed status or name. Other activities carried out by the Weeds Botanist are summarised, as well, such as field trips or presentations to community groups.

The latest reports are now available online:

Brodie, C.J. & Lang, P.J. (2024). Regional Landscape Surveillance for New Weed Threats Project, 2021-2022: Annual report on new plant naturalisations in South Australia (2.7mb PDF).

Brodie, C.J. & Lang, P.J. (2024). Regional Landscape Surveillance for New Weed Threats Project, 2022-2023: Annual report on new plant naturalisations in South Australia (3.2mb PDF).

Also available for download are reports for the year 20-2021 (2.2mb PDF), as well as the reports for 2019-20 (16mb PDF), 2018-19 (4.2mb PDF), 2017-18 (4.5mb PDF), 2016-17 (3.8mb PDF) and a compilation of all reports from 2010 to 2016 (3.7mb PDF).

These reports highlight to land managers, which non-native plant species have recently been found in South Australia and where. New records are listed as either “naturalised/established” (*) or “questionably naturalised/established” (?e).

At the end of June 2023, there were 5170 vascular plant taxa recognised in South Australia, of which 1714 are weeds, i.e. 33%. In the 2021-22 financial year, eight new weeds were added to the Census; and in 2022-23, 15 new weeds. During the last thirteen years, 267 new weed records were added to the SA Census through work of the State Herbarium’s Weed Botanist.

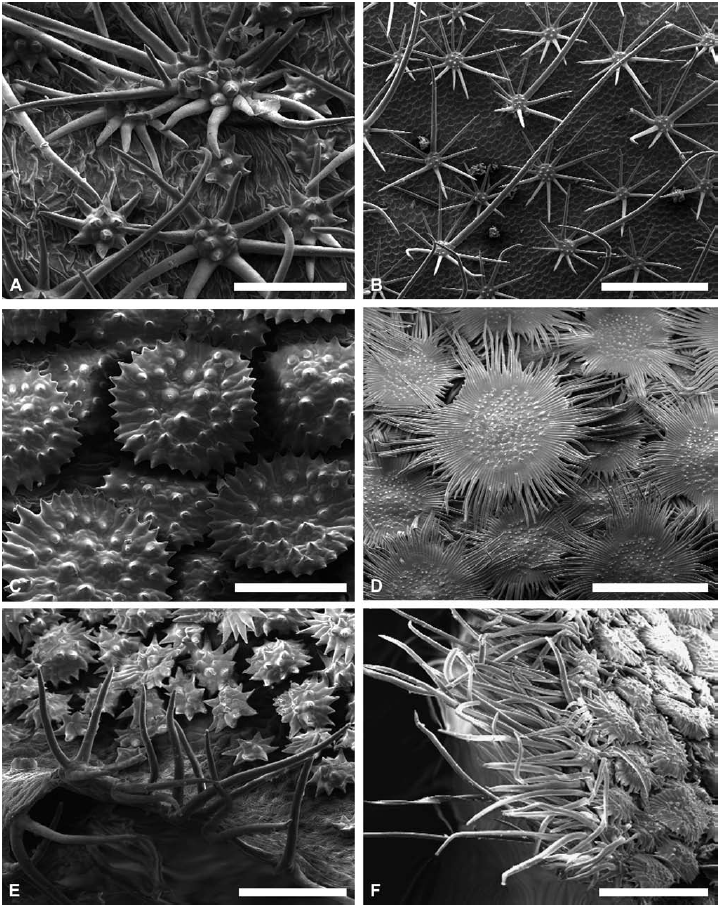

Naturalised plant taxa are those that have originally been introduced by humans to an area, deliberately or accidentally. They have self-propagated without aid, where they are not wanted, and are possibly spreading by natural means to new areas. An example listed in the recent reports recorded as naturalised for the first time, is the garden plant Opuntia leoglossa (Lion’s Tongue ) a species of unknown origin recorded as a weed across Australia and Spain. This is an example of a garden plant that has become weedy (see also a 1985 article by P.M. Kloot; 733kb PDF).

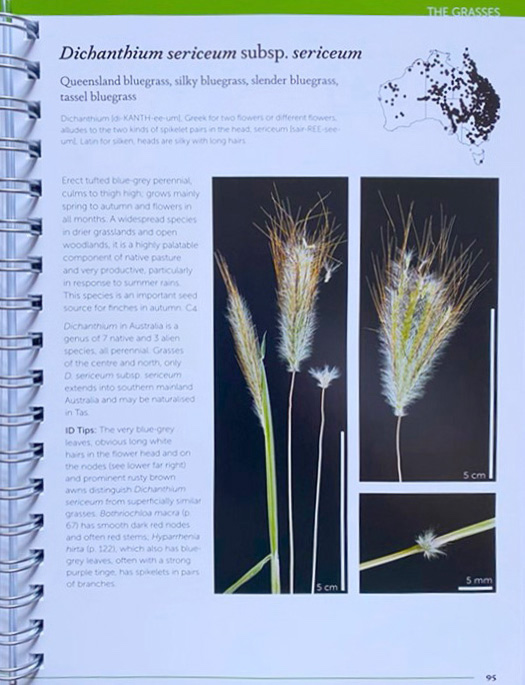

Questionably Naturalised taxa (i.e. possible new weeds) are introduced non-native plants that may be self-propagating without aid, but are not well established or lack data to classify them as naturalised. Examples of this are the garden plants Alstroemeria psittacina Parrot Lily, Nassella trichotoma Serrated Tussock Grass, and several Protea species; Protea neriifolia Oleander-leaf Protea, and Protea cynaroides King Protea.

Australian species can also become weeds, such as Acacia gonophylla Rasp-stemmed Wattle, Banksia grandis Bull Banksia, Melaleuca diosmifolia Green Honey-myrtle, and Vincetoxicum barbatum Bearded Tylophora, all from other states.

The new state records Protea neriifolia Oleander-leaf Protea, Protea cynaroides King Protea, and Banksia grandis Bull Banksia, were recorded for the first time for South Australia collected from Kangaroo Island, from within a fire a scar from the 2019-20 bushfires. Also collected from KI, mostly from within the fire scars were an additional 41 new regional weed records listed as naturalised or questionably naturalised for KI. This data is contained within the “Updates to weed distribution, weed status, and name changes” sections of the reports.

The Mexican palm Washingtonia robusta, growing in an abandoned and demolished part of Leigh Creek. Photo: C.J. Brodie.

Any unknown weed or possible new state or regional weed records should be reported to Chris Brodie (0437 825 685, chris.brodie@sa.gov.au). If you have permission from the landowner, you could press a plant, record collection data, and submit a preserved plant specimen for identification.

The pressed plant (or part of the plant) should consist of stems with leaves attached and preferably flowers and/or fruit. Collection data includes, plant location, habitat, frequency, height and width, colour and smell, and what the plant looks like when alive and growing. Images can help in identifying plants. Also include the date, your name and contact details.

Please use the pro-forma collection sheet (0.4mb PDF) in pencil and submit it together with the pressed plant specimen.

Compiled by State Herbarium Weeds Botanist Chris Brodie.

You must be logged in to post a comment.