In late March 2016, Danielle Calabro, a Ranger at Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island, was digging up Bridal Creeper (Asparagus asparagoides) when she came across a dark brownish-black, monstrous lump approx. 0.5 m underground. Danielle dug it up and contacted Pam Catcheside, Hon. Research Associate at the State Herbarium of South Australia, who works on fungi, to ask if she knew what it was. Pam was able to tell her that it was a sclerotium, a tuber of one of the ‘fire fungi’, Laccocephalum mylittae. Danielle reburied the sclerotium and in late June she, Pam and others (David Catcheside, Flinders University, Helen Vonow, State Herbarium, and Teresa Lebel, National Herbarium of Victoria) who were over in Flinders Chase surveying fungi, went to dig up the fungus.

Sclerotium of Laccocephalum mylittae, held by Danielle Calabro and Pam Catcheside at excavation site, June 2016. Photo: David Catcheside.

Danielle had found the sclerotium in sandy soil under the branches of a fallen Eucalyptus cladocalyx in a disturbed, burnt area of the park. When exhumed, it was found to weigh 7.2 kg and measure 27 × 24 × 19 cm. The interior is white, marbled and solid. It was taken back to Adelaide and dried. Half will return to Flinders Chase, to be put on display at the Flinders Chase visitor centre. The remainder will be kept as an herbarium specimen (PSC 4459, AD-C60004).

Laccocephalum mylittae (Cooke & Massee) Núñez & Ryvarden, native bread, is one of the phoenicoid, the fire fungi, that fruit only after fire. In the case of L. mylittae the mushroom-like fruit body may emerge within a few days after fire.

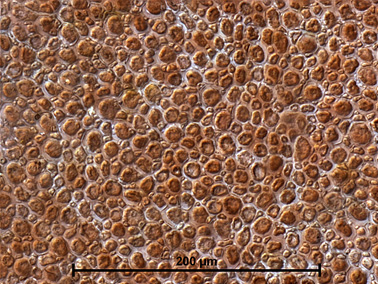

Native bread is a member of the basidiomycete family, Polyporaceae. The whole fruit body is white to cream, often soil-stained. It consists of a cap which may reach 200 mm diameter, is irregular, flat to dome-shaped, smooth, soft but tough. It has pores, not gills, which are small and rather irregular. The stem is central to slightly off-centre, varies in length and diameter and is tough and solid. It leads down to a sclerotium, an underground tuber which has a dark brown to black skin and a white, marbled interior. Texture is rubbery initially but becomes hard and rather tough. The sclerotia may weigh up to 20 kg.

Laccocephalum mylittae is a saprotroph, breaking down woody substrates. It is a brown rot fungus, so called because it rots the wood, resulting in a brittle brown cubical mass.

Fire stimulates the sclerotium to send up a fruit body. This produces spores which, if they land on a damp log, will germinate and form a mycelium, a mat of fine tubes called hyphae. The mycelium proliferates through the log and into the wood, sending the break-down products into the developing sclerotium, rather like the formation of a potato tuber. This sclerotium remains dormant under the soil, sometimes to depths of 0.5 m, until the next fire.

Laccocephalum mylittae produces a true sclerotium, one that is composed of only hyphal matter. Others of the so-called stone fungi, such as L. basilapiloides and L. tumulosum, produce a false sclerotium, one that is mixed with soil and grit.

References

- Kalotas, A.C. (1996). Aboriginal knowledge and use of fungi. In Orchard, A.E. (Exec. Ed.), Mallett, K. & Grgurinovic C. (Vol. Eds.). Fungi of Australia, Vol. 1B: Introduction-Fungi in the Environment. (Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra). (Pp. 284-286, as Polyporus mylittae).

- Robinson, R. (2007). Laccocephalum mylittae – Native Bread. Fungus Factsheet 18 / 2007. (Dept of Environment & Conservation, WA) (500KB pdf).

See also fungi references listed in July’s Plant of the Month blog post.

Contributed by Hon. Research Associate Pam Catcheside.

Plenary speaker

Plenary speaker

You must be logged in to post a comment.