September 1st is Wattle Day, so the State Herbarium of South Australia has chosen golden wattle, Acacia pycnantha Benth., as the plant of the month for Belair National Park, DEWNR‘s Park of the Month (the history of the park is described in this chapter in Valleys of stone)

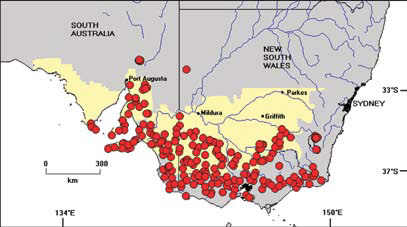

Acacia pycnantha is a variable species that naturally occurs from southern New South Wales west to the Flinders Ranges and Eyre Peninsula, and is common in Belair National Park. Inland plants have a tendency to form slender small trees with narrow phyllodes and pale flowers, while those in wetter coastal habitats grow into larger trees with broader phyllodes and deep golden flowers.

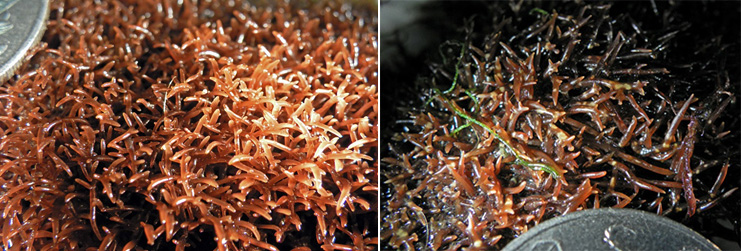

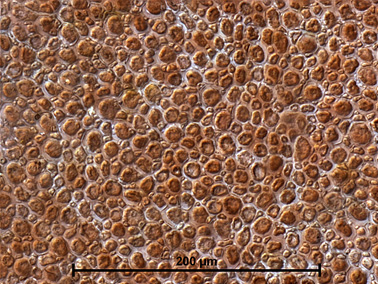

Acacia pycnantha is widely cultivated and has become a weed in Australia and many countries around the world. In the 1980’s Trichilogaster signiventris wasp galls with young were sent to South Africa from Adelaide Botanic Gardens as a biocontrol. This introduction was a success and seed production was greatly reduced — the wasps lay eggs into the developing flower heads which produce galls that prevent seed formation.

In 2011 & 2012 African researchers visited the State Herbarium and conducted fieldwork with staff, revisiting the original collection site and genetically sampling populations across the range of A. pycnantha in Australia. The success of the wasps from South Australia was found to be due to the similarity with the weedy plants in South Africa, where other introductions had failed (see Annals of Botany 111: 895-904).

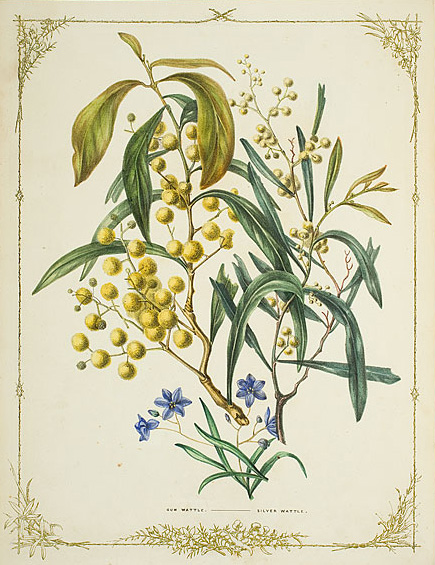

Acacia pycnantha (left) and A. provincialis (right). Fanny de Mole, Wildflowers of South Australia, 1861. Image: National Library of Australia.

The gum of Acacia pycnantha was an important summer food for the indigenous Nations where the plant occurred. This was noticed by the European settlers around Adelaide and the export of gum became an early industry. Fanny de Mole illustrated the species as one of the gum wattles in her 1861 book Wildflowers of South Australia.

Another important industry of the time was wattle bark for tanning, with Acacia pycnantha bark considered to be one of the richest tanning barks in the world. This resulted in extensive clearance of this common species. Later plantings of the species were conducted with limited success, and eventually Australia’s industry was out-competed by South Africa. Today Australia imports most of its tannin requirement, over $6 million per annum.

In 1988 Acacia pycnantha was officially proclaimed the Australian floral emblem and in 1992 the first of September was proclaimed as Wattle Day. However the desire for an Australian floral emblem and day of celebration had a long history. In 1889 the Adelaide branch of the Australian Native’s Association (exclusively male) suggested the formation of a Wattle Blossom League. In 1891 a Wattle Blossom Banner was publically displayed for the first time in Adelaide in connection with Foundation Day ceremonies. 1899 saw the formation of a Wattle Club in Victoria with outings on September first. In 1910 the South Australian and Victorian branches of the Wattle Day League were established, and the first Wattle Day was celebrated in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide on September first. In 1912 the Adelaide branch of the Wattle Day League called for the golden wattle to be the national flower and emblem of Australia. In 1915 the first memorial for the First World War in Australia was erected by the Wattle Day League in the southwest parklands at “Wattle Grove”. In 1919, Henry John (Harry) Butler dropped a golden wattle plant by parachute from his plane into Wattle Grove (presumably the first planting by plane). The League and Wattle Day gradually petered out after World War Two, in part being replaced by Arbour Day.

Contributed by State Herbarium botanist Martin O’Leary.

You must be logged in to post a comment.