July’s Park of the Month, Cleland Conservation Park, commemorates renowned naturalist and mycologist Professor Sir John Burton Cleland, Professor of Pathology at the University of Adelaide. The “Plant” of the Month is not a plant but a fungus, Cortinarius austrovenetus, and is an appropriate choice since it was described by Cleland.

Cortinarius austrovenetus. Photo: David Catcheside.

Cortinarius austrovenetus is a handsome, medium-sized agaric, a gilled fungus. Its green, yellowish-green to bluish-green cap (pileus) may reach 80 mm diameter, is slightly domed but may become flattened. The surface is dry with a silky sheen giving it its common name of green skinhead. The gills (lamellae) on which the spores are produced are initially yellowish but become rusty-brown as the spores mature. The stem (stipe) is yellow to yellow ochre, dry and rather stout, measuring up to 80 mm in height and to 15 mm in diameter. On the upper part of the stem the remains of a cobwebby veil may have a dusting of rusty spores. The cobwebby veil is called the cortina, hence the generic name Cortinarius. It initially protects the developing gills until the spores are mature. The specific epithet is derived from the Latin auster, southern, i.e. Australasian, and venetus meaning sea-coloured. The spores are ellipsoid, measure 9 to 12 µm by 5 to 7 µm and the surface varies from warty-rough to almost smooth.

Cortinarius austrovenetus. Photo: David Catcheside.

Cortinarius austrovenetus is mycorrhizal with many species of Eucalyptus and grows on the ground in native forests and woodlands. It occurs in the southern States: Tasmania, Victoria, New South Wales, Western Australia, as well as South Australia.

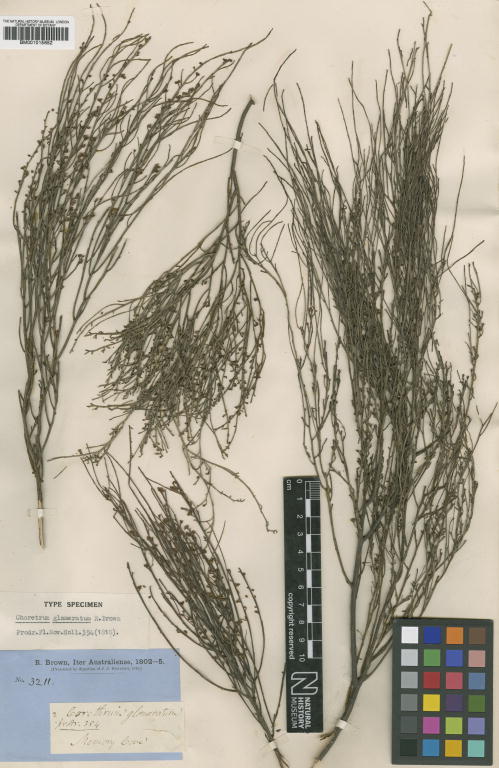

J.B. Cleland collected C. austrovenetus at a number of locations in South Australia: Belair National Park, Kuitpo and Lobethal. The lectotype is from Mount Lofty. The fungus has a wide distribution in South Australia, having been found from parks on Kangaroo Island, the South-east and Northern and Southern Lofty regions, including Cleland Conservation Park.

The State Herbarium of South Australia (AD) houses J.B. Cleland’s approximately 16,000 fungal collections, over 200 of which were new species described by him.

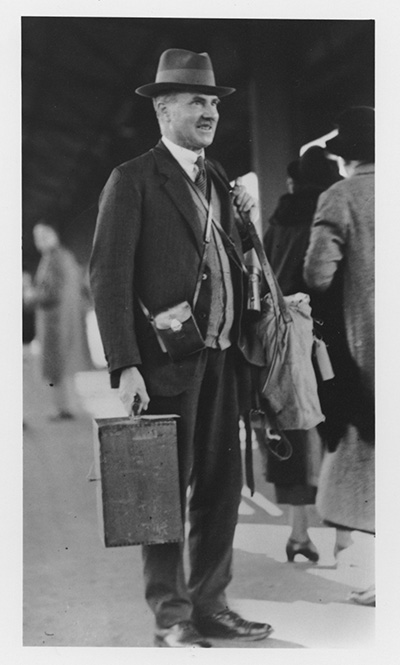

J.B. Cleland Kt., C.B.E., M.D., Ch.M., F.R.A.C.P. was born at Norwood, South Australia in 1878. He developed a love of natural history at an early age, an interest which continued throughout his long life. He died in 1971 at the age 93.

Cleland was a polymath, knowledgeable about botany, geology, ornithology, anthropology, as well as mycology. He decided to study medicine, but, because of problems in administration of medicine at the University of Adelaide, completed his medical training at the University of Sydney. He graduated in 1900, then travelled as a ship’s surgeon to northern Australia and the Far East, went on to train in the United Kingdom in pathology, bacteriology and tropical medicine. He returned to Australia in 1905, initially to Perth, then to Sydney in 1909. While in Sydney he made many collections of fungi and collaborated with Edwin Cheel, a staff member at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney. Together, they described a number of new species of fungi. Cleland returned to South Australia and was appointed Marks Professor of Pathology in 1920, a position he held until his retirement at the age of 70 in 1949.

J.B. Cleland at Adelaide Railway Station with his collecting gear, 1934. Photo: State Herbarium collection.

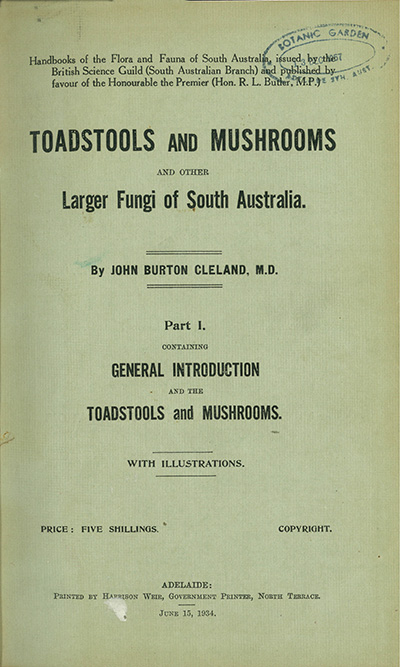

In spite of his responsible position, Cleland devoted much time to collecting, especially to the collecting of fungi. He corresponded with mycologists around the world including E.M. Wakefield at Kew, G.H. Cunningham in New Zealand and C.G. Lloyd in the U.S.A. Most of his collections from South Australia were made from 1920 to 1935. His Handbook, Toadstools and Mushrooms and other Larger Fungi of South Australia, published in two parts in 1934 and 1935, is a major monograph on Australian fungi and the first work covering the larger fungi in this country since M.C. Cooke’s Handbook of Australian Fungi, published in 1892.

Cleland played a large part in the establishment of the Handbooks of the Flora and Fauna of South Australia and was instrumental in the publication of J.M. Black’s Flora of South Australia. He served on many semi-government committees, advising the government on matters of wildlife conservation about which he was passionate. It was largely due to his efforts that National Parks and reserves such as Belair and Flinders Chase National Parks were established.

Professor Cleland was a remarkable mycologist, naturalist, promoter of natural history and his work has enriched our knowledge and understanding not only of the mycology but of the whole South Australian biota.

Important references to S.A. fungi

Important references to S.A. fungi

- Cleland, J.B. (1928). Australian fungi: notes and descriptions. No. 7. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 52: 217-222.

- Cleland, J.B. (1934-1935). Toadstools and Mushrooms and Other Larger Fungi of South Australia, Parts I and II. Government Printer, Adelaide (Reprint 1976).

- Fuhrer, B. (2005). A field guide to Australian Fungi. (Bloomings Books: Melbourne).

- Gates, G., Ratkowsky, D. (2014). Field Guide to Tasmanian Fungi. Tasmanian Field Naturalists Club.

- Grey. P., Grey. E. (2005). Fungi down Under. Fungimap.

- Grgurinovic, C.A. (1997). Larger Fungi of South Australia. The Botanic Gardens of Adelaide and State Herbarium & The Flora and Fauna of South Australia Handbooks Committee. [An up-date of Clelands handbook].

- Shepherd, C.J. and Totterdell C.J. (1988). Mushrooms and Toadstools of Australia. Inkata Press.

- Young AM (2005). A Field Guide to the Fungi of Australia. Sydney, UNSW Press.

You must be logged in to post a comment.