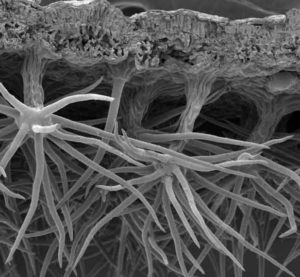

Fungi play important roles after fire. Their fine, root-like hyphae bind soil particles, stabilising the soil and reducing erosion. Fungi provide nutrients for plants, helping to re-establish plant communities. They reduce the high pH of the ash bed. Many fungi break down the burnt litter and wood, returning nutrients to the soil. A previous Blog on fires and fungi in Flinders Chase National Park was written before a recent survey of the Park.

In mid-July 2020, Pam and David Catcheside surveyed the fungi in Flinders Chase National Park, devastated after the previous summer bushfires. These surveys augment those made after the 2007 bushfires in the Park (see references below) and enable comparisons to be made of the fungi fruiting after those fire events. In 2020, 96 % of Flinders Chase was burnt, more than the 85 % estimate for the 2007 fires. Preliminary analysis suggests that, although there is some overlap between the species that occurred after the 2007 and 2020 fires, there are differences both in species composition and species richness, perhaps reflecting the differences in severity of the fires.

In 2020, collections were made at a number of sites, all of which had been severely burnt: near Rocky River, Platypus Waterholes, the Ravine des Casoars, Gosselands and Kelly Hill Conservation Park. The fungi were similar at all sites, though fruiting was less at Gosselands and at Kelly Hill.

Disc fungi made up most of the fungi that were found. These fungi are important colonisers often fruiting in profusion soon after fire. They reduce the strongly alkaline pH (around pH 10) resulting from the ash closer to neutral (pH 7), a pH more favourable for plant growth. The most common species were a fawn to pinkish-brown species of Peziza, possibly P. petersii, black-brown Plicaria recurva (see images above) and the small, brilliant orange Pulvinula archeri. There were a few patches of orange Anthracobia maurilabra and A. muelleri.

After the 2007 fires, Anthracobias were abundant, often in circles around the bases of Xanthorrhoea semiplana var. tateana in contrast with the few patches seen in 2020. Also after the 2007 fires Pulvinula archeri, though present, was not in the profusion found in 2020. Disc fungi are often difficult to identify to species. Almost all require microscopic examination of often nuanced characters such as spore ornamentation. Samples of some of the disc fungi collected have been taken for molecular sequencing and analysis. Results should help to clarify the tentative identifications made so far on the collections.

A few gilled fungi were found, including a species of Laccaria. Laccarias are early colonisers of burnt and bare ground and are mycorrhizal, forming essential partnerships with plants.

In contrast with the fungi found after the 2007 fires, there were few fruit bodies of ‘stone fungi’, species of Laccocephalum. Their hard, pored, mushroom-like fruit bodies come up almost immediately after fire from a sclerotium, an underground storage tuber. This year, fruit bodies of Laccocephalum tumulosum, the only species of Laccocephalum found, were much smaller than those seen after the 2007 fires, reaching only 5 cm in comparison with the up to 20 cm of the 2008 collections. In 2008 and 2009 five species of Laccocephalum were collected: L. tumulosum, L. mylittae, L. basilapiloides, L. minormylittae and L. sclerotinium. Their sclerotia can be mixtures of fungal tissue and sand (false sclerotia) or consist only of fungal tissue (true sclerotia).

At one site at the Ravine des Casoars, an undescribed species of coral fungus, Ramaria or Ramariopsis, was pushing up the sandy soil over an area of several metres. When excavated, this fungus was seen to have a false sclerotium, a structure previously unknown for any species of coral fungus (see images below).

Fungal fruiting is rain and temperature dependent and it is difficult to select the optimal time for surveys and collections. June and July are usually good months for fungi in South Australia. In 2008 Pam and David spent a week in early June when they collected 14 species of disc fungi, approximately 17 species of gilled fungi, two boletes (soft pored fungi with a central stem), a few club, bracket and coral fungi, in all approximately 40 species. The conditions prior to their collecting trip in 2020 were dry and would have had a somewhat detrimental effect on fungal fruiting. Nonetheless, the results were unexpected: only nine species of disc fungi, four of gilled fungi, two coral fungi with a total of 18 species. These preliminary results from the two sets of surveys suggest that both species composition and richness are less after the more extensive and more severe summer fires of 2020.

References

- Catcheside, P.S. (2009). The phoenicoid discomycetes on Kangaroo Island. Fungimap Newsletter 38: 5–7 (1.2mb PDF).

- Catcheside, P.S., May, T.W. & Catcheside, D.E.A. (2009). The larger fungi in Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island. Surveys 2008. Report for Wildlife Conservation Fund and Native Vegetation Council.

- Catcheside, P.S. & Catcheside, D.E.A. (2010). The larger fungi in Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island. Surveys 2009. Report for Wildlife Conservation Fund and Native Vegetation Council.

Contributed by Pam Catcheside (State Herbarium Hon. Associate)

& David Catcheside (Flinders University).

You must be logged in to post a comment.