Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite 'em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum.

And the great fleas themselves, in turn, have greater fleas to go on;

While these again have greater still, and greater still, and so on.

Augustus De Morgan, A Budget of Paradoxes (1872)

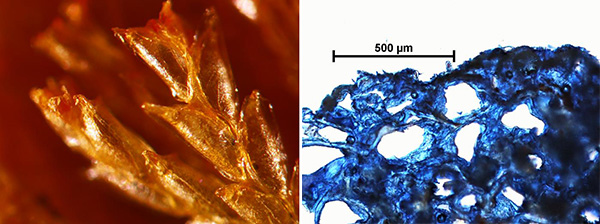

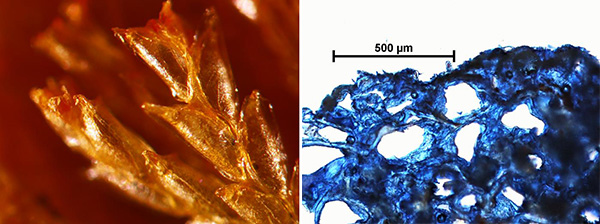

The apparently simple specimen that proved to be a whole community of marine organisms. Photo: B. Baldock.

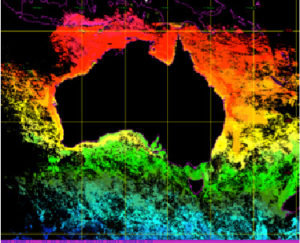

This small specimen was collected from 21 m deep waters, at St Francis Island, Nuyts Archipelago, South Australia (see also South Australia’s offshore islands, p. 150; 33mb PDF). It was torn from its substrate by the frame of an underwater Baited Remote Underwater Video Station (BRUVS) used to film fish populations as part of the survey of Marine Parks, and was given to the Phycology Unit of the State Herbarium of South Australia in 2015.

LEFT: Remains of the slightly calcified exoskeletons of individual zooids in the bryozoan colonies. RIGHT: Part of the inter-connected chambers of the tree-like sponge, walls stained blue. Photo: B. Baldock.

At first sight I thought the specimen was simply a group of “moss animals” or bryozoans (probably Canda arachnoides Lamouroux, above left). But closer inspection proved that the bryozoans were growing on a tree-like sponge full of inter-connected chambers (above right).

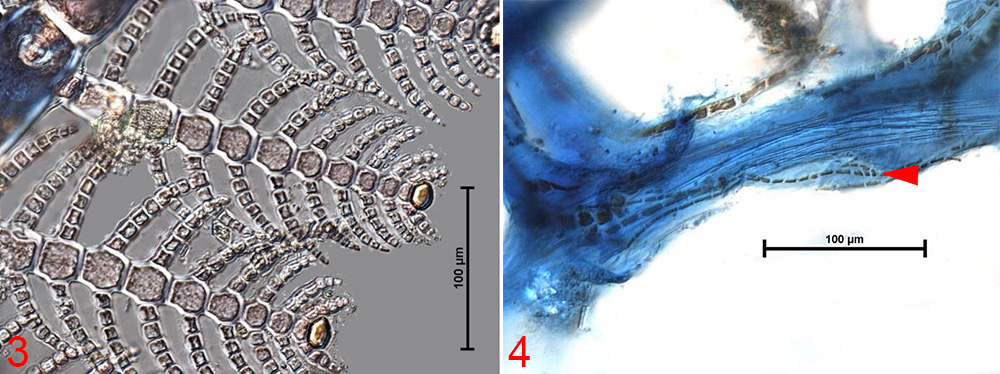

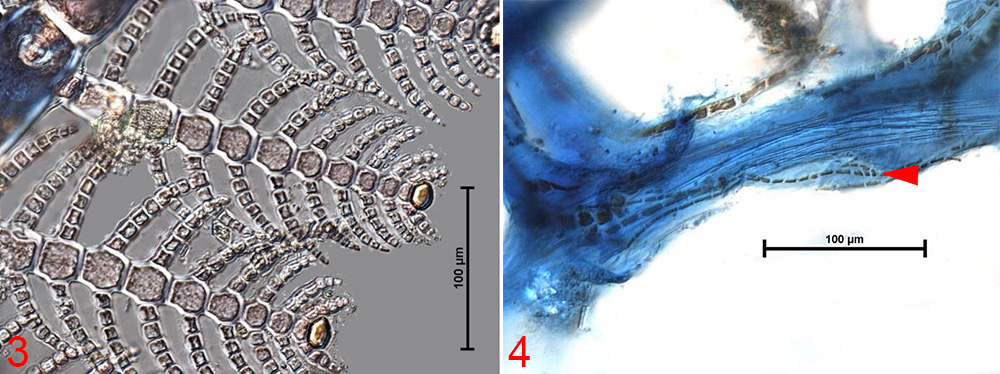

In addition, under the microscope, I found four algae – a veritable community coating the sponge. Labelled with red numbers 1 to 4 in the images, below.

(1) Dictyopteris gracilis, delicate sporelings attached to a sponge skeleton (top), which is stained blue, and a single flimsy blade (bottom). (2) Lejolisea aegagropila, female structure (top) and stalked sporangia (bottom), stained blue. Photo: B. Baldock.

The largest, a Brown alga, Dictyopteris gracilis Womersley (no. 1), consisted of sporelings “babies”, getting established on a relatively stable, hard substrate, a requirement for most algae to survive. They could have grown into quite elegant, leaf-like plants some 200 mm tall. Their growing centres (meristems) are found in the notch at the apex of the delicate filmy blades. See the Algae revealed factsheet for the species (420kb PDF).

In addition, there was a tangled set of microscopic pink threads, Lejolisia aegagropila (J. Agardh) J. Agardh (no. 2), easily recognised from its female reproductive structures (procarps and cystocarps) that resemble glass light-bulbs. Mixed in with the female plants was another stage in the species life cycle – a spore plant with packets of 4 spores (tetrasporangia) on minute stalks.

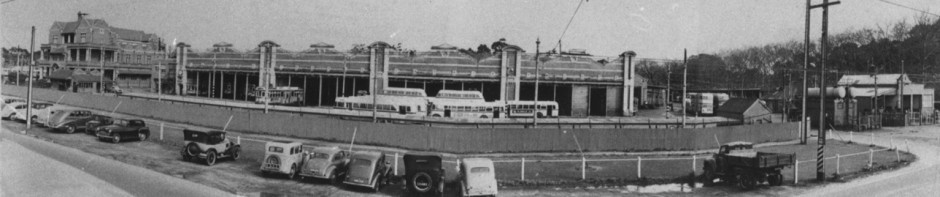

(3) Acrothamnion preisii, elegant feathery (pinnate) side branches tipped with a glistening gland. (4) Audouinella spongicola, minute threads of the Red alga (arrow), running along the blue-stained walls of the sponge which shows ,also, needle-like skeletal spicules. Photo: B. Baldock.

Perhaps the most striking, however, was the Red alga Acrothamnion preissii (Sonder) Wollaston, with its elegant “feathers”, each ending in a glistening gland (no. 3).

The most unusual alga, although obscure, consisted of lines of elongate red cells (no. 4) running on the surface and around the walls of the inter-connected sponge chambers. These belonged to threads of a very simple Red alga, Audouinella spongicola (Weber van Bosse) Stegenga, which, as its name denotes, specifically lives on sponges.

The common, single-celled foraminiferan Discorbis dimidiatus, its shell punctured with minute pores, lives amongst the algae attached to the sponge. Photo: B. Baldock.

There were other microscopic organisms: shell-like unicellular animals (foraminifera), diatoms with glassy walls; and inevitably, bacteria, but I stopped investigations at the plants and animal described above, thinking I had enough evidence to support the sentiment in the adage at the start of this article.

I hope the BRUVS people can continue to send more, minute but nevertheless interesting marine communities to us at the State Herbarium. You never know what will turn up in the marine world.

Contributed by State Herbarium Hon. Associate Bob Baldock.

Bush Blitz is an innovative partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia. It is the world’s first continent-scale biodiversity survey, providing the knowledge needed to help us protect Australia’s unique animals and plants for generations to come.

Bush Blitz is an innovative partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia. It is the world’s first continent-scale biodiversity survey, providing the knowledge needed to help us protect Australia’s unique animals and plants for generations to come.

You must be logged in to post a comment.