Laver – a delicate red alga favoured as the wrapping around rice for sushi has appeared in a distinct, dark band of growth on boulders of the artificial breakwater of the Sea Rescue Marina(Barcoo Inlet), near West Beach, Adelaide.

The species is Porphyra lucasii Levring. Uninspiring at first glance, a sheer, purple, frilly blade about 50 mm long can be seen if the alga is floated out in water.

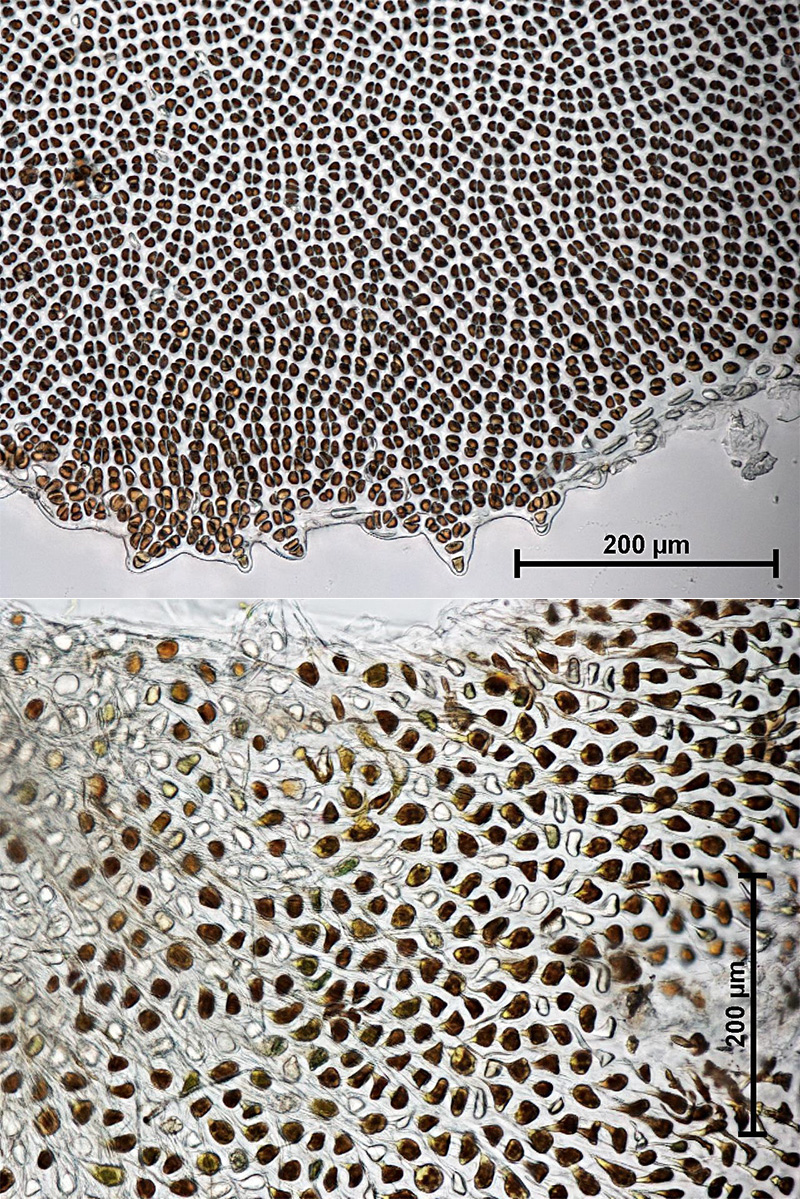

It is more spectacular under the microscope – one cell thick with dazzling patterns of cells and a toothed blade edge. It clings to the rocks by a patch of cells (a “holdfast”) with snake-like projections that squeeze into minute crevices in the rock surface.

In southern seas, we see Porphyra only in winter. At the State Herbarium of South Australia, we have metropolitan Adelaide specimens from Port Stanvac and Brighton jetty piles, and Witton Bluff, Port Noarlunga.

Pophyra lucasii. Microscopic view of a blade edge (top) and holdfast cells with thread-like “tails” (bottom). Photo: B. Baldock.

But Porphyra has a secret life, not yet detected locally in the wild: a microscopic, thread-like spore phase. This is called a Conchocelis stage and gets its name because the tips of its threads penetrate shells of molluscs (“concho” meaning something to do with shells). – The discovery of this lifecycle in another species of Porphyra by British phycologist Kathleen Mary Drew-Baker in 1949 revolutionised seaweed production in Japan.

An unusual feature of the West Beach plants is their high position in the intertidal – merely in the “splash” zone, or “supra-littoral”, above high tide. Do they survive because seas have been so rough recently and they occasionally get splashed? In some places, the plants sit on a mat of seagrass fibres about 5 mm thick. Could this act like a sponge and sustain the alga with water at low tide and during calmer conditions?

Unfortunately, the band will disappear with the coming of summer, the conditions drying and shrivelling the delicate plants. Next winter, will they return?

Contributed by Bob Baldock and Carolyn Ricci, Phycology Lab., State Herbarium.