Throughout the decades the staff at the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium have collected and curated plant specimens from all over the State. This enables the State Herbarium to document the native and introduced plant species that occur in South Australia.

The Herbarium’s collections contains more than one million plant specimens from all over the world; of these, more than 600,000 are South Australian plant specimens. In the early 2000s the State Herbarium of South Australia along with all other Australasian herbaria catalogued their Australian native plant collections and shared the data via a free online database, called the Australasian Virtual Herbarium.

This publicly available data based on the physical specimens in the herbarium collection allows current and future botanists to understand our flora in an ever growing way. Here, I have generated biodiversity assessments of the South Australian flora presented as maps of high diversity areas using all of the information in these collections.

By dividing South Australia into 10km grid cells, it is possible to calculate, which areas in the State contain the greatest number of plant species (richness), and which ones contain the greatest number of plants that are unique to South Australia (endemism). These maps show that both the Adelaide Hills and Kangaroo Island are two significant floral diversity areas for South Australia.

The maps present results that display one of the reasons why the fires that occurred in late 2019 and early 2020 may be a concern for the future of South Australia’s plant biodiversity. We can visually observe some of the reasons for concern by overlaying the locations of the past summer’s fires onto maps of South Australian plant species richness and South Australian plant endemism (see below, using data from NASA FIRMS).

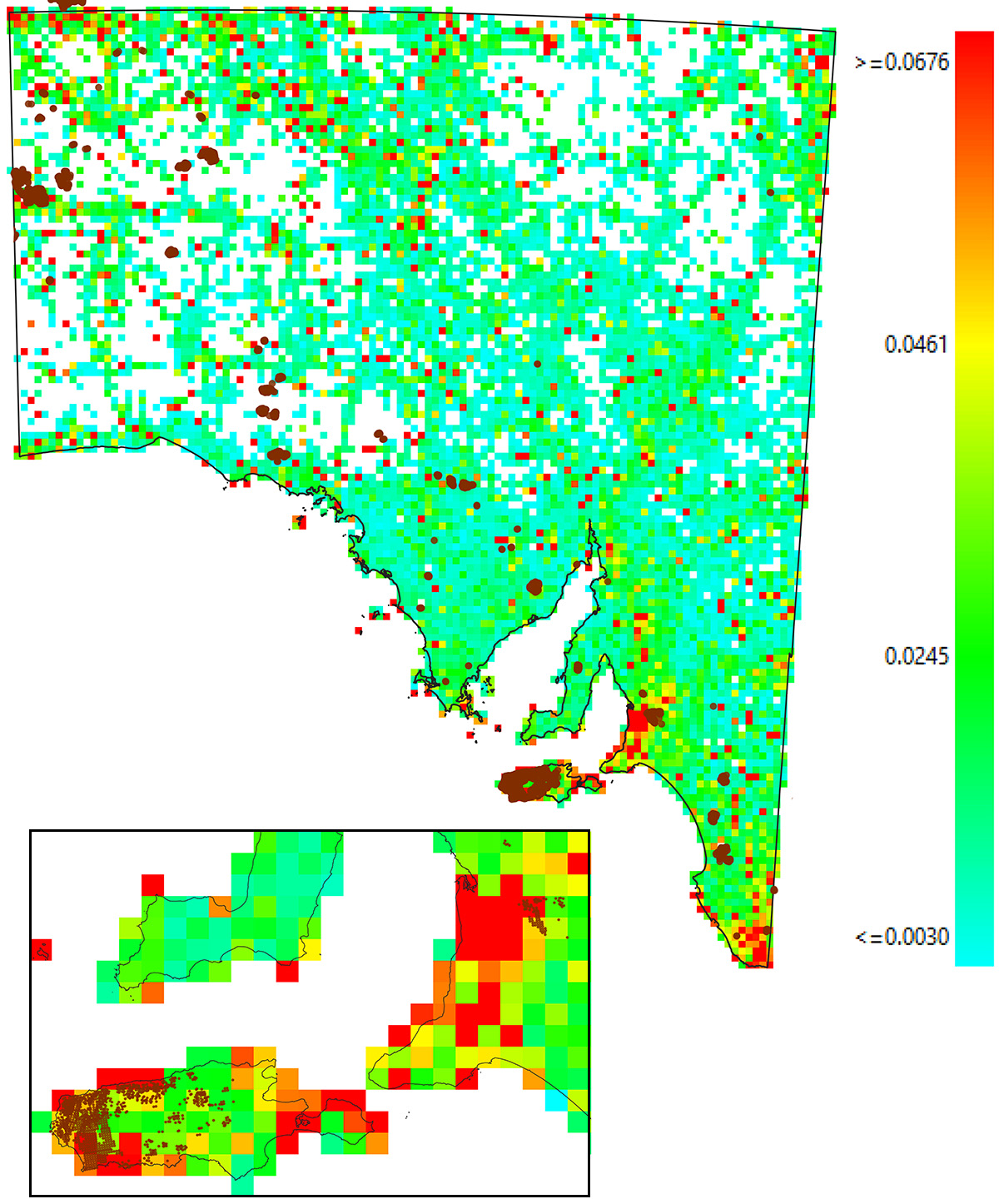

Richness

The figure below is a map of South Australian plant species richness. The majority of areas that contains the most species (i.e. the areas in red) is higher mountain regions such as the Flinders Ranges and the Adelaide Hills, as well as the Eyre Peninsula, Kangaroo Island, and the south-east.

A species richness analysis of South Australian plants using plant records from all Australasian herbaria collected since 1802. Grid cells are 10 × 10 km2. Where the fires of 2019/2020 occurred are the brown dots. The inset box shows Kangaroo Island and the Adelaide Hills and the dots represent fire areas of December 2019 and early January 2020. It can be seen that many of the high plant diversity cells of the western and northern parts of Kangaroo Island have been severely impacted by the fires.

Zooming in on the fire areas of Kangaroo Island and the Adelaide Hills, it can be seen that the fire has occurred in areas that contain some of the highest number of plant species in the State. The Adelaide Hills fires have burnt across a smaller number of the map grid cells in comparison to the Kangaroo Island fire. The Adelaide Hills fires still occurred in areas of high plant diversity.

The Kangaroo Island fires burnt across the majority of species rich cells on the western half of the island, but it is also important to note that many of the species that grow on the western end of Kangaroo Island are very different to those that grow on the eastern side of the island (which was mainly unburnt).

To analyse this in more detail, the second measure becomes important, i.e. endemism.

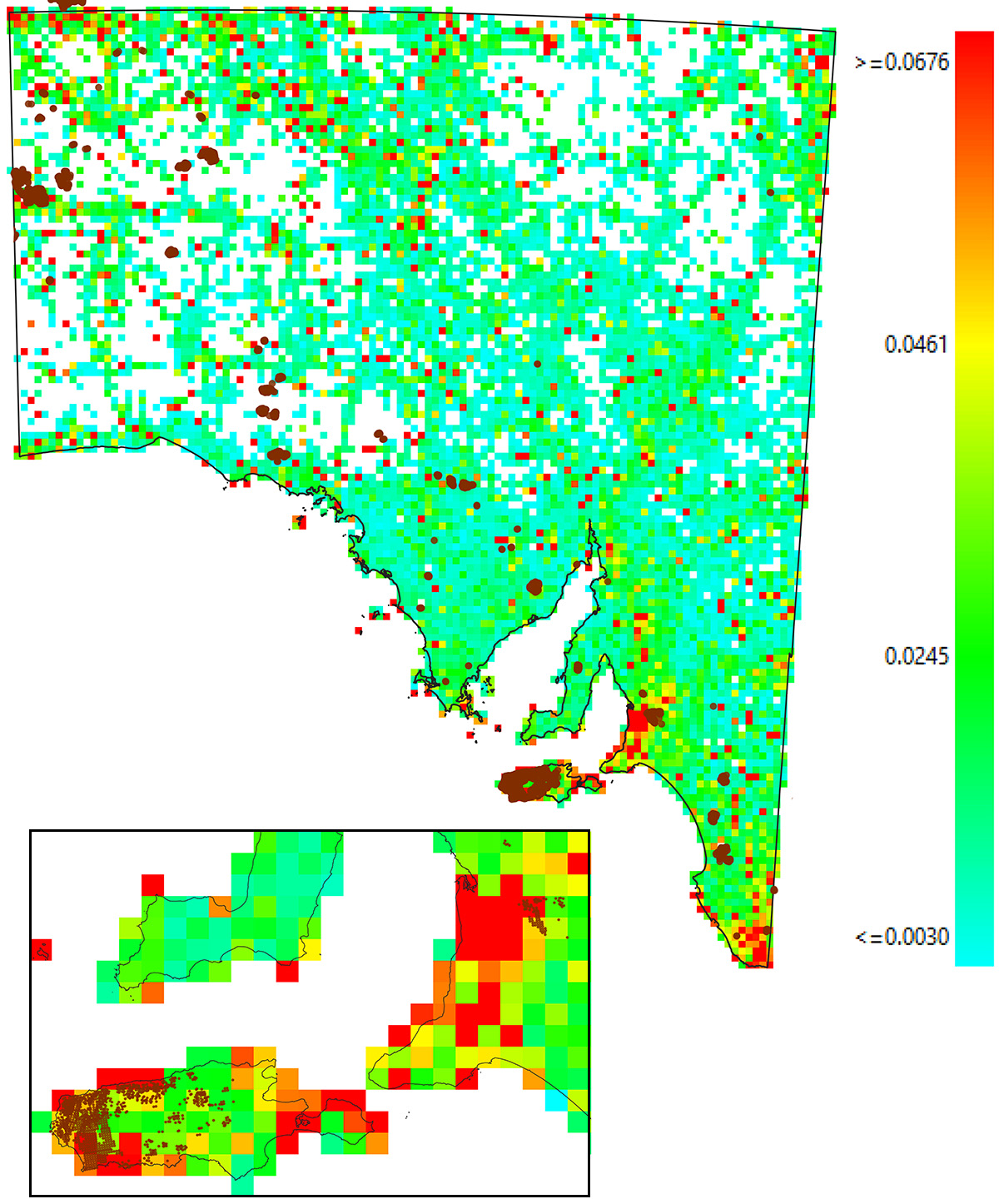

Endemism

South Australia has three significant concentrations of plant endemism – Kangaroo Island, Adelaide Hills and south-eastern South Australia. As can be seen in the figure below, the map cells with significant endemism in the western region of Kangaroo Island have been impacted by the fires. Part of the significant Adelaide Hills endemism has been burnt in the fires. The endemism area in the South-East of the State has not been affected by fire so far.

An endemism richness analysis of South Australian plants using plant records from all Australasian herbaria collected since 1802. Grid cells are 10 × 10 km2. Where the fires of 2019/2020 occurred are the brown dots. The inset box shows Kangaroo Island and the Adelaide Hills. South Australia has three significant concentrations of plant endemism – Kangaroo Island, Adelaide Hills and South-eastern South Australia. As can be seen the significant endemism cells of western Kangaroo Island have been impacted by the fire. Part of the significant Adelaide Hills endemism has been burnt in the fires.

It will be important that during the remainder of this autumn, no more fires occur in areas of high diversity or endemism. In particular, fire in the south-eastern part of South Australia would be problematic for plants that are unique to South Australia, even though some of these plants occur in Victoria on the other side of the State border.

Recovery of native vegetation

There have been significant bushfires in the past, e.g. there was a major fire on Kangaroo Island in 2007 that burnt most of the western side of the island. The Ash Wednesday fires of 1983 in the Adelaide Hills was also a significant fire event. In those instances the vegetation recovered over time.

As the cooler and wetter weather in autumn and winter continues, plants will begin to recover and germinate. Many Australian natives are adapted to recovering from fire and the eucalypts will soon start sprouting leaves from their epicormic buds or lignotubers, while grass trees will send up new shoots. Some plants are advantaged by fire and there will be mushrooms, mosses, sundews, and orchids that will appear over the forest floor in numbers.

As for some of the rare and endemic species on Kangaroo Island, we won’t be able to say for certain until it is safe enough to re-enter the areas where they occur, and probably until next spring, when flowering begins and plants can properly be identified; or even a year or two after that.

We have plant lists for many parts of Kangaroo Island which have been collated over the years through the work of the Kangaroo Island community, students, State Herbarium staff, the S.A. Seed Conservation Centre and many volunteers. These lists and locations will assist with understanding the recovery processes of the fire affected areas over the coming years.

Remarkable Rocks on Kangaroo Island post-fire (10 Jan. 2020). Photo: DEW.

Written by Andrew Thornhill, State Herbarium of South Australia & The University of Adelaide.

You must be logged in to post a comment.