A group of botanists from the State Herbarium of South Australia had an interesting find while walking in Adelaide Botanic Garden recently. Chris Brodie, a botanist specialising in non-native plants of South Australia was scanning around, always on the lookout for weeds. In the crack between two brick pavers he saw a tiny plant and got down on hands and knees for a closer look. Carolyn Ricci, Tracey Spokes and Peter Lang came over to see what he had found, all were down peering at the tiny green plant. The sight of four mature adults crawling around on the pavers attracted some strange glances and extreme social distancing from passers-by! The plant was very small and intriguingly no one knew for sure what it was. Chris took some photos on his smartphone of an entire plant and zoomed in on the strange dark markings on the leaves.

Seeing the magnified images, Peter suggested the dark leaf areas might be a fungal infection. Carolyn located further specimens nearby, it was then noted to be reasonably common in that area. A sample was taken for investigation.

On returning to the State Herbarium, Chris took a look at the sample under a microscope and was pleased to see the sample contained both flowers and fruit (these are often necessary for accurate identification of plant species). The plant was identified as a species of Callitriche. The fruit are the definitive characters for identifying species in this genus. The plant was not a weed at all, but a native species named Callitriche sonderi (formerly in Callitrichaceae, now in the family Plantaginaceae). A check of the SA Plant Census revealed the species is currently listed as Rare in South Australia.

Peter used a digital image stacking process using a camera attached to a microscope to increase the depth of field shown in the macroscopic images of the plant.

It is good practice to look at other specimens in the collection to confirm identifications, and a search revealed that most of the Herbarium’s Callitriche specimens had been loaned to Richard V. Lansdown, a researcher at Kew and a world expert on the genus. Fortunately the loan had recently been returned and was being processed prior to its placement back in the vault. (Herbarium policy requires return loan material to be frozen to exterminate any pests that may have infiltrated the specimens in transit prior to returning to the collection). An Australian treatment published in 2007 by A.R. (Tony) Bean at the Queensland Herbarium indicated some changes to existing species concepts. Using the key to all Australian native and alien Callitriche species in Bean’s revision, and referring to the re-determined loan specimens returned from Kew, Peter and Chris were able to confirm that the pavement specimen remained within the species concept of Callitriche sonderi.

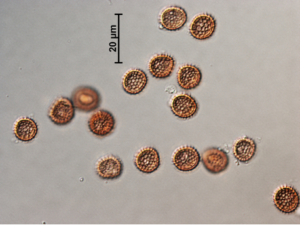

Meanwhile Teresa Lebel, a mycologist and specialist in truffle-like fungi, Agaricus and Russulales at the State Herbarium, was consulted regarding the dark markings on the leaves and confirmed Peter’s hunch that it was indeed a fungal infection, most likely a smut fungus. Teresa, Carolyn and Bob Baldock took pictures of the fungal spores using a compound microscope with an attached camera. During this process they discovered an abundance of pollen, predominantly Pinus spp. and a few moss spores. Teresa consulted a colleague — Roger Shivas, a Plant Pathologist and Mycologist with a specialty in rusts, smuts and other microfungi at the Plant Pathology Herbarium at the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Roger referred Teresa to a smut fungus Doassinga callitrichis found on Callitriche stagnalis in Germany, this being the only known smut/Callitriche association in his experience. However, Teresa’s investigations revealed that the Botanic Gardens smut does not affect the Australian Callitriche in the same way, and microscopically does not resemble the description of Doassinga callitrichis. Teresa and Roger are now planning a collaboration to research this potentially new species of smut fungus and new plant/fungal association.

While walking through the botanic gardens Tracey found another population of Callitriche sonderi growing between the pavers some 200 metres from the first find. This leaves us wondering if Callitriche sonderi is rare in South Australia or, because of its small size, it is rarely seen and collected.

Written by Herbarium staff member

Tracey Spokes.

Dr James’ research interests focus on the diversity and biogeography of the flora of the Pacific region. For more than six years, she has been undertaking field work in Papua New Guinea and, recently, the Solomon Islands, collecting new botanical specimens in remote locations, and digitising herbarium collections from the Pacific. Now working for iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections), the US initiative mobilising biological specimen data, she liaises between museum collections staff, researchers, educators and cyberinfrastructure to promote the use of natural history collections and the data they contain in answering big science questions.

Dr James’ research interests focus on the diversity and biogeography of the flora of the Pacific region. For more than six years, she has been undertaking field work in Papua New Guinea and, recently, the Solomon Islands, collecting new botanical specimens in remote locations, and digitising herbarium collections from the Pacific. Now working for iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections), the US initiative mobilising biological specimen data, she liaises between museum collections staff, researchers, educators and cyberinfrastructure to promote the use of natural history collections and the data they contain in answering big science questions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.