A number of mushrooms that fruit at the start of the autumn are fungi that have been introduced to Australia with their non-native tree hosts. These are the ectomycorrhizal fungi that have hitch-hiked to Oz on the roots of pines, firs, birch, oaks and willows. Ectomycorrhizal fungi form an obligate symbiosis with the roots of their host trees, providing water and access to nutrients that the plant roots can’t get too, and in return receiving food in the form of sugars that the fungus can’t make for itself.

In the early days, plants were transported to Australia as seedlings or small trees, sometimes as bare root stock, or at times in a pot of soil. The native fungi in Australia cannot form these symbioses with the non-native trees, so it was critical that these ectomycorrhizal hitch-hikers came along for the ride, enabling the establishment of some lovely trees.

Ectomycorrhizal roots (LEFT) and a cross-section of a root-tip showing the ‘sock’ of fungal hyphae surrounding the root and penetrating in between root cells (blue staining; RIGHT)

While the identity of species fruiting with oaks, pines and birch are reasonably well known, there are still surprises, and very little known about the ectomycorrhizal hitch-hikers that grow with willows. Unfortunately while there are some edible mushrooms in the mix, there are also some poisonous species, including the deadly toxic Amanita phalloides or deathcap. If you see any of these poisonous mushrooms, then please lodge photos in our iNaturalist fungisight project. This will help provide a better idea of how widely these mushrooms are distributed.

Amanita phalloides grows only with oaks, chestnut & hazelnut in Oz. Caps are generally greenish yellow, shiny, 3-10 cm wide. Gills white. Stem has a ring or skirt, and a bulbous sac (volva) that the stem sits inside at the base.

POISONOUS — One of the most poisonous of all known mushrooms, a piece the size of a 20c piece or a small button is enough to cause serious organ damage or fatality. The principal toxin is α-amanitin, which damages the liver and kidneys, causing liver and kidney failure, in people and pets.

Amanita phalloides. Photo: T. Lebel.

Amanita phalloides. Photo: T. Lebel.

Amanita muscaria grows with birch, pines, & oaks. Caps are red to orange with white flecks on top, 8-20 cm wide. Gills white. Stem has a ring or skirt and a bulbous base.

POISONOUS — Contains several active compounds, muscimol a psychoactive and ibotenic acid a neurotoxin. Deaths from this fungus have occurred but are rare.

Amanita muscaria (composite image). Photo: R. Halling.

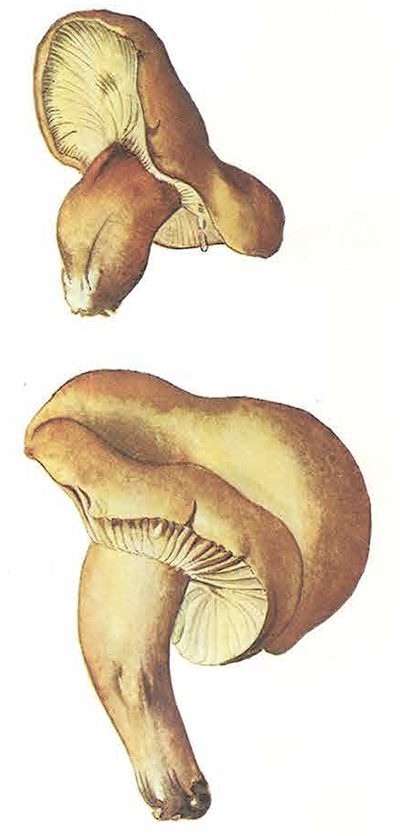

Paxillus involutus grows with birch, oaks, hazel, & pines. Caps are various shades of brown, funnel-shaped up to 12 cm wide with a distinctive inrolled rim. Gills slightly lighter in colour than the cap, running down the stem (decurrent) (see also images on the Kaimai Bush page).

POISONOUS — An antigen in the mushroom triggers the immune system to attack red blood cells. People can consume the mushroom for years without any other ill effects, before suddenly becoming seriously to fatally ill.

Paxillus involutus. Photo: T. Lebel.

Lactarius pubescens grows with birch. Caps are a blend of pink and brownish, sometimes with concentric zones of alternating lighter and darker shades, often with a central depression, up to 10 cm wide. The edge of the cap is rolled inward, and shaggy when young. Gills are a similar colour to the cap. When cut or injured, the fruit bodies ooze a bitter white milk (see also information on the First Nature page).

POISONOUS — This species is highly irritating causing mild to severe gastro. The toxins, also responsible for the strongly bitter or acrid taste, are typically destroyed by cooking or long preparation.

Lactarius pubescens (LEFT), close-up of gills and edge of cap (RIGHT). Photos: T. Lebel.

Lactarius turpis / necator typically grows with birch, but can grow on pine & spruce. Caps are olive brown or yellow-green and often sticky or slimy, with an inrolled margin and velvety zones when young. Cap becomes funnel-shaped and darkens to blackish in age, up to 8–20 cm wide. Gills dirty white, stained olive-brown by old milk, running slightly down the stem (see also information on the First Nature page).

NOT RECOMMENDED — Very bitter/acrid tasting and contains a mutagen nectorin.

Lactarius turpis. Photo: T. Lebel.

If you suspect you or someone you know has eaten a wild mushroom, do not wait for symptoms to appear. Contact the Poisons Information Centre on 13 11 26 for advice and always call triple zero (000) in an emergency.

Written by State Herbarium mycologist Dr Teresa Lebel.

You must be logged in to post a comment.