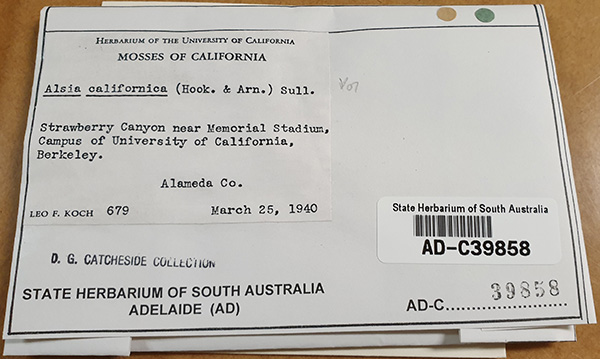

In the middle of 2019, I began developing a project to make a database of the South Australian bryophyte collection. There are over 30.000 bryophyte specimens in the State Herbarium of South Australia (AD), most of them stored in envelopes with the information typed or hand written on to the front of the envelope (like most bryophyte collections in herbaria). All of the envelopes had accession numbers but very few of them had barcodes or were databased.

With the help of Nunzio Knerr from CSIRO we developed some scripts that would read printed barcodes from a digital image and put the barcode number in the file name. Another script read any typed information and turned it into a text file. At the same time I was told about DigiVol, an Australian initiative that has citizen scientists transcribe scientific information, such as institute collections or camera-trap images. With the help of Eleanor Crichton and Ainsley Calladine from the State Herbarium we developed a bryophyte transcription template to capture the information from each envelope.

The second stage was the biggest part of the project. At the end of 2019 and start of 2020 we began the task of recording accession numbers of each envelope, printing out a barcode, sticking the barcode onto the envelope, and taking a photo of each envelope.

With the help of summer student scholars Joel Bowes and Sam Billings, as well as weekly volunteers Catherine Courtney and Bonnie Newman we started off with a bang and were processing around 500 envelopes a day. A number of test DigiVol “expeditions” were created, and we began to transcribe the envelopes with the idea that we would iron out errors before making the expeditions live.

At the end of March 2021, Covid-19 hit Australia and everything came to a screeching halt. No volunteers could come to the herbarium nor staff. What had started off so promising had now stopped. We had around 2.000 envelopes already imaged and set up as expeditions, but they were yet to be made live. At the end of April 2020, it was decided we should make the expeditions live and see what happen

The first expedition with 477 envelope images was made live in May. It was completed in five days. The second expedition was made live and finished just as quickly. Soon, we started running out of a bank of images. In mid-May there were a slight lifting of restrictions and we were allowed to return to work or one or two days a week. I made the decision that I would take the images by myself to try and keep ahead of the DigiVol volunteers. From June to October, I imaged around 15.000 envelopes and just managed to stay ahead of the volunteers, who transcribed at a rapid rate.

In November it was agreed that Bonnie could return as a volunteer and with her help the imaging productivity skyrocketed. By the end of 2020 we had barcoded and captured the image of 24.000 envelopes. At the start of January 2021, I dedicated two weeks to finish the remaining 6.000 envelopes, which we completed at the end of January.

State Herbarium bryophyte volunteers and student scholars busy at work. Photo: A. Thornhill.

As it currently stands the DigiVol volunteers have transcribed over 25.000 envelopes, which is about 80% of the collection. The transcribing is likely to be finished by the end of March at our current rate. Once this is done we will curate our records and then the information will be made available through the Australasian Virtual Herbarium.

When I designed the project I had no idea that it would be completed so quickly. The fact that many Australians had not much to do due to lockdown and so turned to DigiVol certainly helped, but it also helped that we had a dedicated team of volunteers, both at the herbarium and online, who dedicated many hours to complete this project so quickly. If you are interested to see what the DigiVol project looks like then it can be viewed here.

Written by State Herbarium botanist Andrew Thornhill.

You must be logged in to post a comment.