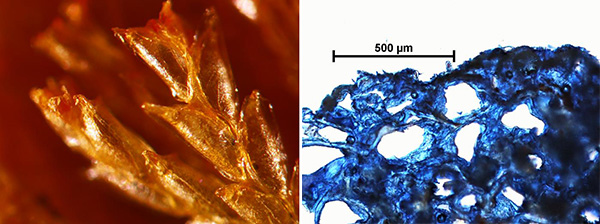

Anthocercis angustifolia in the understorey of a Sheoak woodland in Morialta Conservation Park. Photo: P.J. Lang.

Rays of delight on a rocky path

Anthocercis angustifolia, close-up of flowers. Photo: P.J. Lang.

Our new plant of the month is the rare endemic South Australian shrub, Anthocercis angustifolia F.Muell. (Narrow-leaf Ray-flower). It has a patchy disjunct distribution restricted to a few pockets in the Mt Lofty and Flinders Ranges where it is associated with rocky slopes, escarpments and gorges. One of the best places to see this unusual plant is in DEWNR‘s Park of the Month for August, Morialta Conservation Park. It is currently in flower on the upper walking trail just above Kookaburra Rock lookout and southwards towards the waterfalls. Anthocercis angustifolia is a fire responsive species and it came up in profusion here after this area was burnt several years ago. The illustration above shows it in a successional phase dominating the understorey of an Allocasuarina verticillata Sheoak woodland. The delicate white to creamy-yellow flowers have long narrow corolla lobes from which the genus takes its name based on the Greek anthos, a flower, and kerkis, a ray. When not in flower A. angustifolia may be recognised by its sparse erect habit and slender leaves with small glandular hairs making them clammy to touch. Anthocercis species are known to be poisonous and contain tropane alkaloids.

Anthocercis is a well-defined apparently monophyletic genus comprising c. 11 currently recognised species. Its centre of diversity is in Western Australia, with most species confined to that State. South Australia also has a second species, Anthocercis anisantha, which extends from WA and has a more compact and spinescent habit. Comprehensive fact sheets on this and other Anthocercis species are available under ‘Identification Tools’ on the efloraSA website, together with an interactive Lucid key to Australian Solanaceae. These useful but often overlooked resources were put together by State Herbarium Honorary Associate Robyn Barker. An illustrated Plant Portrait was published in the Journal of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens 7(3) 309-311 (1985) (580kb PDF). Further information can also be found on the Seeds of South Australia web-site and the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA).

Anthocercis angustifolia. Photo: P.J. Lang.

Contributed by State Herbarium botanist Peter Lang.

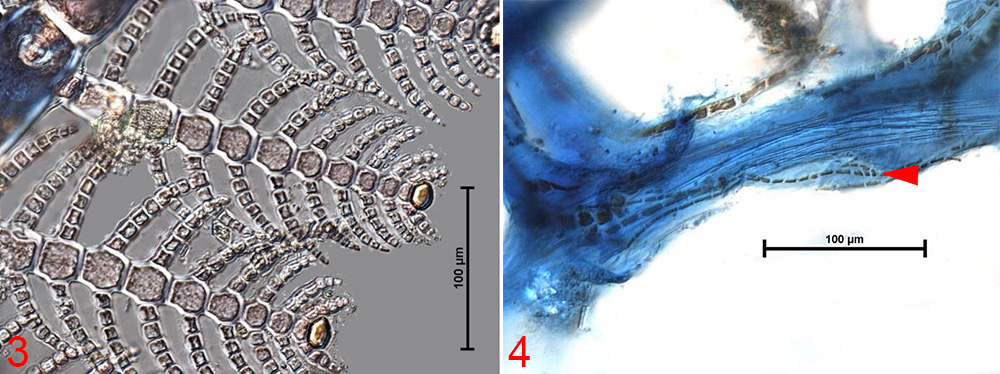

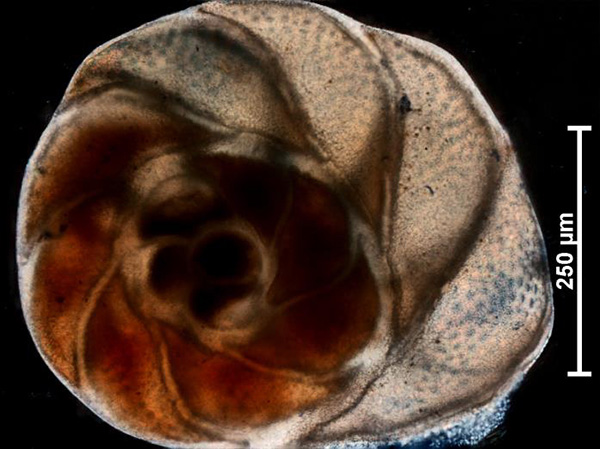

Bryobartramia novae-valesiae and other strange beasts!

Bryobartramia novae-valesiae and other strange beasts!

You must be logged in to post a comment.