The State Herbarium of South Australia‘s Fungus of the Month for May 2017 is Chlorociboria aeruginascens, a species of small disc fungi that is widespread but particularly spectacular in DEWNR’s Park of the Month, Flinders Chase National Park.

Chlorociboria aeruginascens (Nyl.) Kanouse ex C.S.Ramamurthi, Korf & L.R.Batra has a number of common names including ‘blue-green wood cup’, ‘green elf-cup’ and ‘blue or green stain fungus’. It is a common and widespread fungus, growing in groups on debarked wood or fallen branches, causing the wood to be stained a brilliant blue-green colour. The similarly coloured cup-like fruit bodies are found in very moist conditions in the wetter winter months.

The generic name is derived from the Greek kloros (χλωρός), meaning green, and Latin ciborium, a drinking cup. The specific epithet comes from aerugo, Latin for verdigris, a deep bluish-green encrustation formed on copper or brass, and the suffix ascens, becoming.

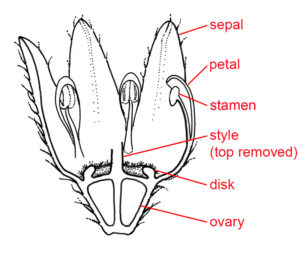

The fruit bodies, apothecia, are tiny, stalked cups to 5 mm high, of an intense turquoise colour. The apothecia have a diameter of 4–10 mm and initially are a shallow cup-shape but flatten to a disc with a slightly raised margin. The blue-green upper surface is smooth to wrinkled with a small dimple; the outer surface is smooth and slightly paler with a white bloom. The tiny stem tapers down and is often off-centre; it is the same colour or slightly darker than the cup and black at the base. The stem bases of the fruit bodies are attached to a black mat of hyphae embedded in the wood.

Chlorociboria aeruginascens is a cosmopolitan, saprotrophic species. In the northern hemisphere it grows mostly on hardwoods, such as poplar, Populus spp., oak, Quercus spp. and ash, Fraxinus spp.; in the southern hemisphere it is on Eucalyptus spp. and Nothofagus spp., although it does grow on other woods. The wood on which it grows is usually soft, giving the appearance that it has been infected by white-rot fungi but C. aeruginascens is not considered a true wood-rot fungus. The blue-green pigment, a quinone derivative called xylindein, is secreted by the microscopic tubular threads, the hyphae, of the fungus. It has been suggested that the pigment may make the wood less enticing for termites and may also reduce competition with other wood-inhabiting fungi.

The green-stained wood was highly prized. It was used in inlaid decorative woodwork such as Tunbridge ware, marquetry, intarsia panels and parquetry. Tunbridge ware was made in Tonbridge and Tunbridge Wells in Kent, England, from the mid-18th century. Small pieces of different coloured woods, including the blue-green wood stained by Chlorociboria aeruginascens, were used to make pictures and patterns and inlaid into small boxes, fire screens and tables. Marquetry involves the glueing of small pieces of coloured wood on to thin veneers for use in furniture-making. Parquetry is a similar technique used mainly for floors. In the older process of intarsia, a solid piece of one material is cut out from a surface such as a table-top or floor and patterns made up of wood, marble, ivory and/or mother-of-pearl are inserted into the excised area (see also this article).

Collection of Chlorociboria aeruginascens (P.S. Catcheside 4378) in the lab before drying. With centimetre scale. Photo: D.E.A. Catcheside.

Chlorociboria aeruginascens is in the family Chlorociboriaceae Baral & P.R.Johnst., order Helotiales Nannf. ex Korf & Lizoň. Seventeen species of Chlorociboria are recognized worldwide, fifteen occur in New Zealand. They may be separated on the basis of spore size and shape, hyphae on the outer surface of the apothecia and on macroscopic differences such as colour of fruit body, some species having a yellow or white disc while some dry orange-brown, others blue-green. Johnston & Park (2005) have described a subspecies from New Zealand, Chlorociboria aeruginascens subsp. australis P.R. Johnst., which is morphologically indistinguishable from a subspecies found in the northern hemisphere, Chlorociboria aeruginascens subsp. aeruginascens. They may be separated only by molecular analysis, an impractical procedure in the field! No molecular work has been done on the specimens illustrated here, but it is probable that they are of Chlorociboria aeruginascens subsp. australis. Only two species from Australia are listed in the ALA, C. aeruginascens and C. aeruginosa (Oeder) Seaver. Both species look very similar, but C. aeruginosa has longer spores and larger terminal cells on the outer surface. An earlier name, Chlorosplenium aeruginascens (Nyl.) P. Karst., still occurs in a number of field guides. (See also Fungi in Australia, Part 2 and references therein; 40.2mb PDF).

Contributed by Hon. Research Associate Pam Catcheside.

You must be logged in to post a comment.