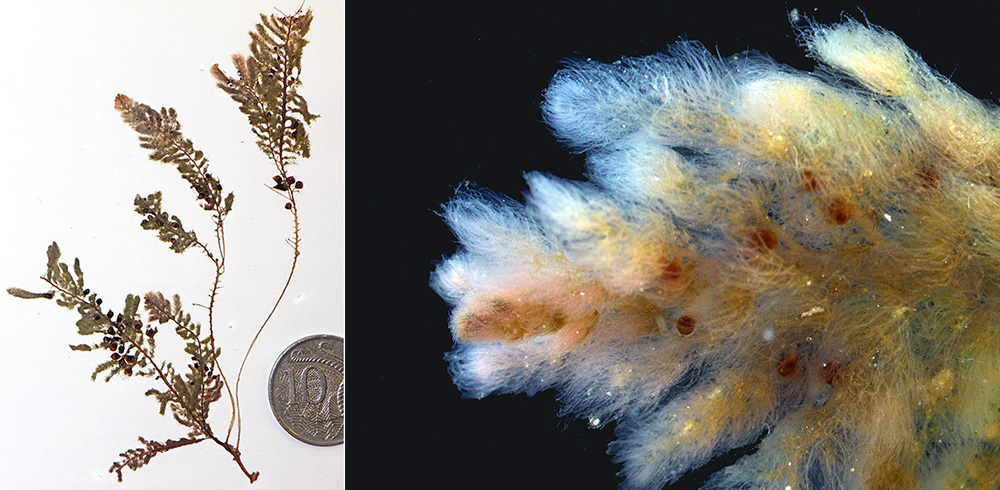

Scutellinia scutellata, Flinders Chase National Park. Scale bar = 10 mm. Photo: David Catcheside.

A small orange disc fungus, Scutellinia scutellata, is the State Herbarium of South Australia‘s Fungus of the Month for October 2017. This little fungus is widespread, but particularly spectacular in DEWNR’s Park of the Month, Flinders Chase National Park. The common name for Scutellinia scutellata is “eyelash fungus”, because of the long dark hairs fringing the margin of the brilliant orange disc.

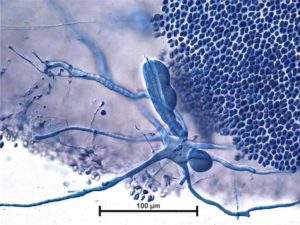

Scutellinia scutellata, Flinders Chase National Park, fresh herbarium collection PSC4233. Each division of scale bar = 1 mm. Photo: David Catcheside.

Scutellinia scutellata (L.) Lambotte is a common disc fungus with a worldwide distribution. It is saprotrophic, growing on rotten, wet wood, sometimes on soil but in association with wood. The fruit bodies may be in clusters or gregarious over the wood.

The generic name is derived from the Latin scutum, a shield, with the suffixes -ella, denoting the diminutive stature, and –ineus, meaning resembling. The specific epithet scutellatum means shield or saucer shaped.

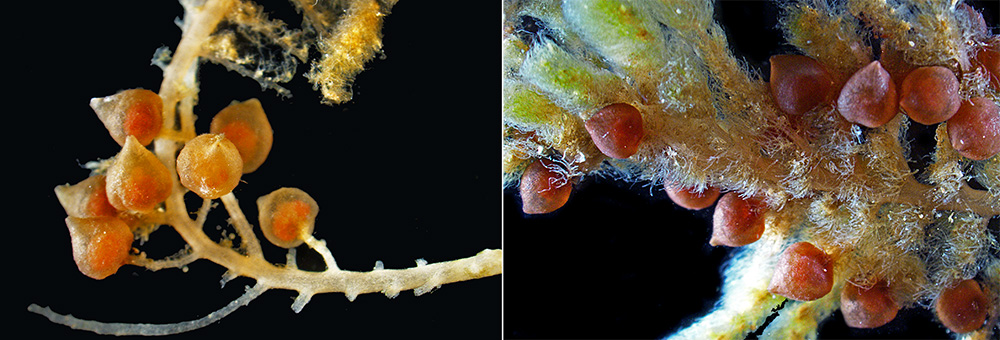

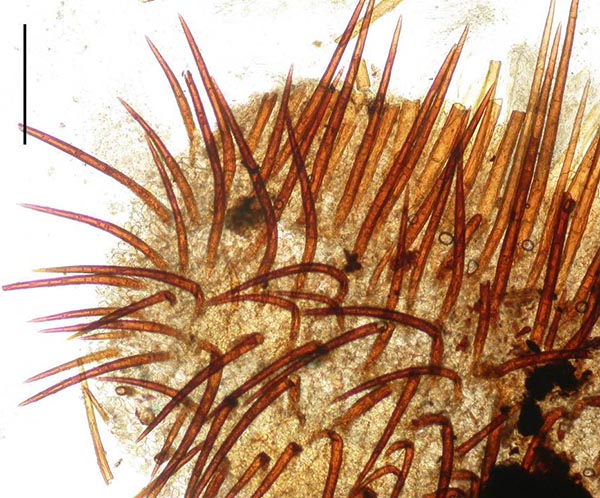

The fruit bodies, apothecia, are small, stemless saucers of height 1–5 mm and diameter 2–10 mm, although they may reach a diameter of 20 mm. The apothecia start as tiny spherical knobs which expand and become saucer-shaped. Later the saucers flatten into discs with upturned margins. The surface of the upper disc is bright orange to orange red, its margin is fringed with stiff, bristle-like black-brown hairs to 1.5 mm long. The lower surface is brownish due to the dense brown hairs.

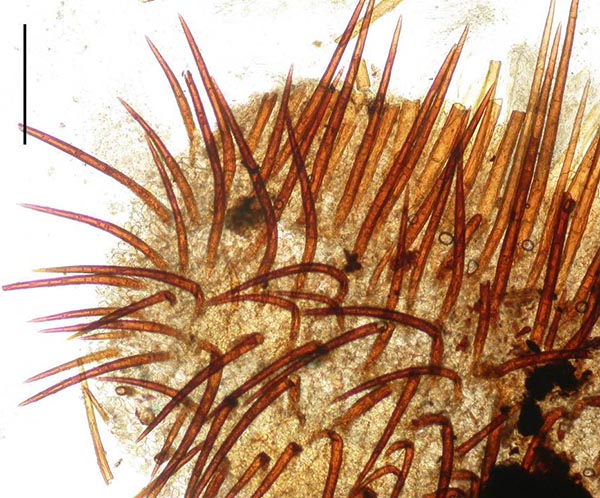

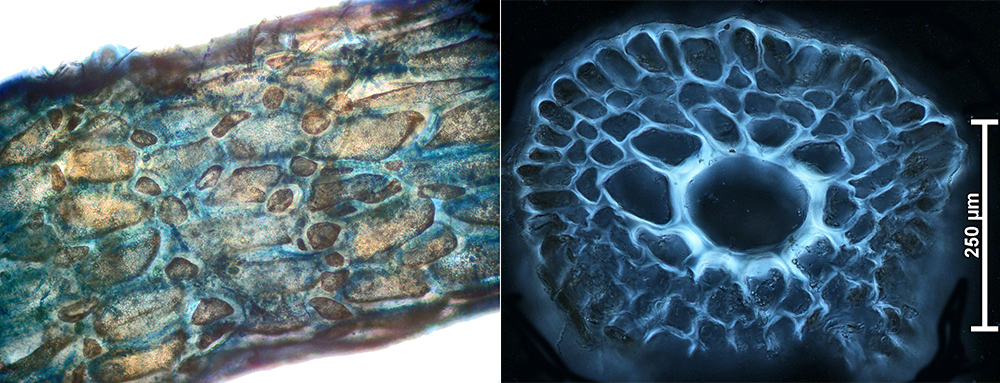

Scutellinia scutellata, hairs on outer surface of apothecium. Scale bar = 10 µm. Photo: Pam Catcheside.

Scutellinia (Cooke) Lambotte is in the family Pyronemataceae Corda, order Pezizales J.Schröt. Sixty-six species of Scutellinia are recognised worldwide, eight occur in Australia. In South Australia, besides S. scutellata, three other species have been recorded: S. kerguelensis (Berk.) Kuntze, S. vinosobrunnea (Berk. & Broome) Kuntze and S. pseudomargaritacea Le Gal.

More information about the species was published online by Michael Kuo (mushroomexpert.com), Mykoweb and Wikipedia.

Other references

Beug, M.W., Bessette, A.E. & Bessette, A.R. (2014). Ascomycete Fungi of North America. University of Texas Press: Austin, Texas. P253-254 (D; CP).

Fuhrer, B. (2005). A field guide to Australian Fungi. Bloomings Books: Melbourne. P337 (D; CP).

Gates, G. & Ratkowsky, D. (2014). Field Guide to Tasmanian Fungi. Tasmanian Field Naturalists Club. P235 (D; CP).

Saunders, B. (2015). Admiring the Fungi of the Lower Eyre Peninsula. Printmax, Government of South Australia, Eyre Peninsula Natural Resources Management Board. P170 (D; CP).

D = description; CP = colour photograph.

Contributed by State Herbarium Hon. Research Associate Pam Catcheside.

You must be logged in to post a comment.