Dr Hellmut Toelken has devoted his career (and ‘retirement’) to the taxonomy and systematics of South African and Australian flora. Over this time he has contributed roughly 6000 collections to African herbaria, and over 3600 to Australian herbaria (of which around 1400 are databased). He named 412 taxa, authored over 72 publications (14 in retirement, mind you), revised two large genera, Crassula and Hibbertia, as well as the Australian species of Kunzea. Hellmut even had one genus names after him, Toelkenia P.V.Heath (now a synonym of Crassula), as well as one species and one hybrid: Kunzea toelkenii de Lange and Kalanchoe xtoelkenii Gideon F.Sm.

Dr Hellmut Toelken has devoted his career (and ‘retirement’) to the taxonomy and systematics of South African and Australian flora. Over this time he has contributed roughly 6000 collections to African herbaria, and over 3600 to Australian herbaria (of which around 1400 are databased). He named 412 taxa, authored over 72 publications (14 in retirement, mind you), revised two large genera, Crassula and Hibbertia, as well as the Australian species of Kunzea. Hellmut even had one genus names after him, Toelkenia P.V.Heath (now a synonym of Crassula), as well as one species and one hybrid: Kunzea toelkenii de Lange and Kalanchoe xtoelkenii Gideon F.Sm.

The 45th anniversary of his first day at the State Herbarium is coming up next month, but where did his journey begin?

From South Africa…

Hellmut was born in Windhoek, South West Africa (now Namibia) and lived on a farm in the bush. The aftermath of WWII made petrol scarce, and therefore overpriced, ruling out the option of a daily 101 km trek to the nearest town of Gobabis for school. Instead he headed off to boarding school in Windhoek, 402 km from home, at the age of 8.

His interest in plants began with gardening on the farm, as well as cultivating flowers and succulents at school, and solidified with a Bachelor of Science from Stellenbosch University (1961), followed by an Honours Degree (1962), Masters (1965), PhD (1974) and even a lecturing position in botany at the University of Cape Town.

During his time in South Africa, Hellmut worked at the Botanical Research Institute in Pretoria on the genus Crassula (Crassulaceae) in particular, authoring the 2-volume A Revision of the Genus Crassula in Southern Africa (1977), based on his PhD thesis. From 1974 to 1976 he was the South African Botanical Liaison Officer at the Kew Herbarium.

To South Australia…

In April 1979, Hellmut immigrated to Australia and had all of two days holiday before commencing at the State Herbarium of South Australia. Not only did he have to adapt to a new country, but also its new and unique environment. He describes a 9-week field trip with fellow State Herbarium botanist Bob Chinnock in Sep. 1979 as being a good (though perhaps intensive) opportunity to become familiar with the flora of his new home.

Fortunately, Hellmut was able to continue researching some of the families and genera he had become an expert on in Africa, such as Crassula and Carpobrotus (Crassulaceae), which are also found in Australia, though sometimes as weeds. As Senior Botanist, he contributed to, and co-edited Flowering Plants in Australia (1983) and the revised, 4th edition of Flora of South Australia (1986). During this time, he also authored the Crassulaceae volume of the Flora of Southern Africa (1985).

Fortunately, Hellmut was able to continue researching some of the families and genera he had become an expert on in Africa, such as Crassula and Carpobrotus (Crassulaceae), which are also found in Australia, though sometimes as weeds. As Senior Botanist, he contributed to, and co-edited Flowering Plants in Australia (1983) and the revised, 4th edition of Flora of South Australia (1986). During this time, he also authored the Crassulaceae volume of the Flora of Southern Africa (1985).

In 1995 he first published research on Hibbertia (Dilleniaceae), particularly eastern and northern Australian species, which has become the primary focus of his research for the past 14 years and earned him renown as a world expert.

Master taxonomist

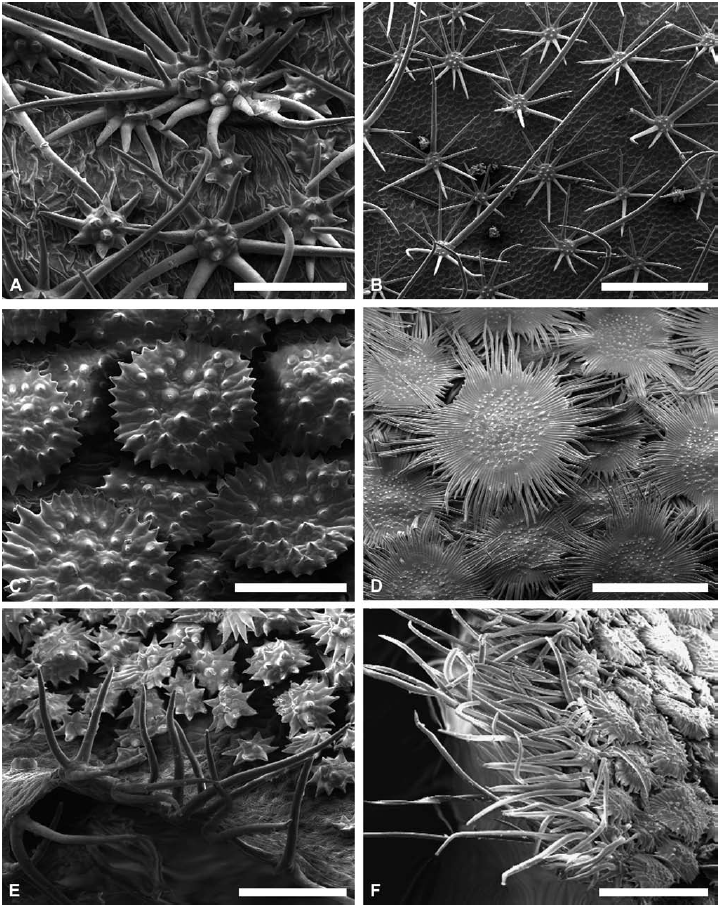

Different hair types in Hibbertia tomentosae group. First published in Toelken, J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. Vol. 23: 6 (2010).

A critical contribution to the taxonomy of Hibbertia was Hellmut’s method for describing, identifying and determining relationships within a large northern Australian group including Hibbertia tomentosa (previously called the “Tomentosae”). Species identification usually begins with morphological characters, such as differences in the organs of a flower. However, Hibbertia flowers can be strikingly similar: often with yellow petals and little obvious variation to the naked eye. Instead, Hellmut looked beyond the flowers to the microscopic trichomes (hairs that occur on many parts of the plants) to separate species. Individually each hair type has a distinct morphology that can be described in detail and differentiated from other hair types: ranging from simple and straight, to hooked, star-like or even scale-like. Using these hairs is invaluable as they provide the diagnostic differences to help separate species, and allows identification in sparse or dated collections.

Hibbertia fumana, described by Hellmut Toelken in 2011 from specimens collected in the early 1800s. Image: G.R.M. Dashorst.

Because a thorough description of a species can lead to further individuals or populations being found, Hellmut’s work has also been pivotal for conservation. Hibbertia fumana (from New South Wales) was thought extinct, before being unknowingly rediscovered as part of a biological survey 190 years after it was first collected. Hellmut realised some of the specimens were the supposedly extinct Hibbertia, and was able to revise its description with much more detail including that of the fruit and seed (which weren’t present in the three original herbarium specimens), illustrations, and photographs. This detailed treatment put the species back on collector radars, and the additional described characteristics allowed for field identification. All of this taxonomic work led to a population of 370 living plants being found, pulling the species well and truly out of extinction. And that is just one of 379 species described by Hellmut!

Hellmut’s advice for budding taxonomists?

Use your initiative and look beyond flowers. He touts the importance of physical collections and morphological examination in tandem with molecular analysis, and says that field trips are the best part of the job.

Written by State Herbarium staff member Jem Barratt.