The 19th of March is a day to teach (or remind) us about the crucial science of taxonomy, and to think of those that practice it.

The 19th of March is a day to teach (or remind) us about the crucial science of taxonomy, and to think of those that practice it.

Associate Professor in Biology Terry McGlynn created Taxonomist Appreciation Day 12 years ago for us to stop and say: Thank you taxonomists!

OK, but what is taxonomy?

As a Know Our Plants reader I’m sure you already know, but taxonomy is the science of identifying, describing, naming, and ordering different species. For us at the State Herbarium of South Australia that might be algae, fungi, vascular plants, or cryptogams like moss and lichen. Without taxonomy, we wouldn’t be able to distinguish separate species or identify what’s out there, let alone research it and ultimately try to conserve it.

If you picture a taxonomist, you may imagine a scientist hunched over a microscope or poring over a lofty stack of books. While that’s not entirely untrue, last year we profiled (and thanked) taxonomist Dr Hellmut Toelken, who divulged that field trips are the best part of the job. Personal field work is common, but taxonomists often also participate in trips to survey or describe a certain taxa or region.

And that’s exactly what we did last year with a field trip over seas!…

To Kangaroo Island

A region known for having more endemism than any other in the state, but equally renowned for the intense bushfires it endured in 2019/20. In February and May 2021 teams from the herbarium first visited sites in Flinders Chase National Park and other western locations to assess fire recovery progress and collect plants as part of the Kangaroo Island Rapid Assessment (KIRA) project. They used their botanical and taxonomical expertise to identify what was growing and recovering (often despite the absence of more easily identifiable characteristics such as flowers and fruit), as well as how they were growing: either resprouting from existing plants or germinating from seed.

In October 2024 we replicated this process to see how the sites had changed and grown almost five years on from the fires.

KIRA 2.0

We had to approach Site 24 from the other direction due to the state of Yacca Flat Track. Photo: Jem Barratt.

This time around our team comprised the herbarium Collection Manager, Senior Scientific Officer (Manager), Molecular Botanist, two Senior Botanists, and two Technical Officers, and we only had four days to resurvey all sites. Well, all accessible sites…

In the end we were able to resurvey 21 sites and collected 985 rows of data! Using the previous survey’s plant list, we recorded absence, presence and reproductive status as well as listing any new species we could find. To accompany the data, we made pressed plant collections of each species with identifiable features. Luckily this time around we didn’t have to dig all the plants up to determine their method of growth.

As a non-botanist, the expertise (and tutelage) of the taxonomists on the trip was invaluable. Helen Vonow, in particular, patiently checked my field identifications and helped me learn to distinguish species within the same genus. It was also interesting to hear Dr Ed Biffin and Helen describe how the sites had changed since their 2021 field work, which was also evident in the prior data. Site 12, for example, had 0% canopy remaining post-fire in 2021, but was impenetrably thick in 2024.

We were forced to reduce our Site 12 search area from roughly 700 m² to 100 m² due to vegetation density. Photo: Jem Barratt.

I also gained insight into the different strategies and fire reliance of plant species. On this follow-up trip 201 plant records from 2021 were now absent – could these be fire obligates, or early succession species, or is something else going on? As well, we added 301 newly observed species to the site lists that weren’t seen in 2021. Such a large change in species composition might tell us something of interest about fire recovery.

Michael Stead, Helen Vonow, and Katherine Ticli trudging onward to the next survey site. Photo: Jem Barratt.

In total we made 460 collections from the sites, mostly of vascular plants but also of moss, lichen, fungi, and algae. After each long day of crunching through the sites in our gaiters and sitting in the sun pressing hundreds of plants, we worked into the night snipping leaf samples for later DNA analysis, data entering the scribbled (and sometimes rained on) data sheets, and finessing and thinning the presses.

The individual research interests of each botanist also led to opportunistic collecting from additional sites. Dr Jürgen Kellermann was hunting for Spyridium (Rhamnaceae), while Dr Tim Hammer was on the lookout for every Hibbertia (Dilleniaceae) he could find. Katherine Ticli was also on board, which allowed for some novel seagrass collections.

Although I’m not a taxonomist, I wholeheartedly agree with Hellmut that field work is a highlight! I learned a lot about the different habitats and plant communities of western Kangaroo Island, and that was just from the field work itself. Imagine what will come to light once we finish processing and determining (identifying) the specimens, and analysing the data. The comparison with 2021 (and earlier) data may help us understand how resilient KI plant communities are, how they change over time, how they respond to fire, and how we can use that knowledge to reduce the impact of future fires.

Stay tuned.

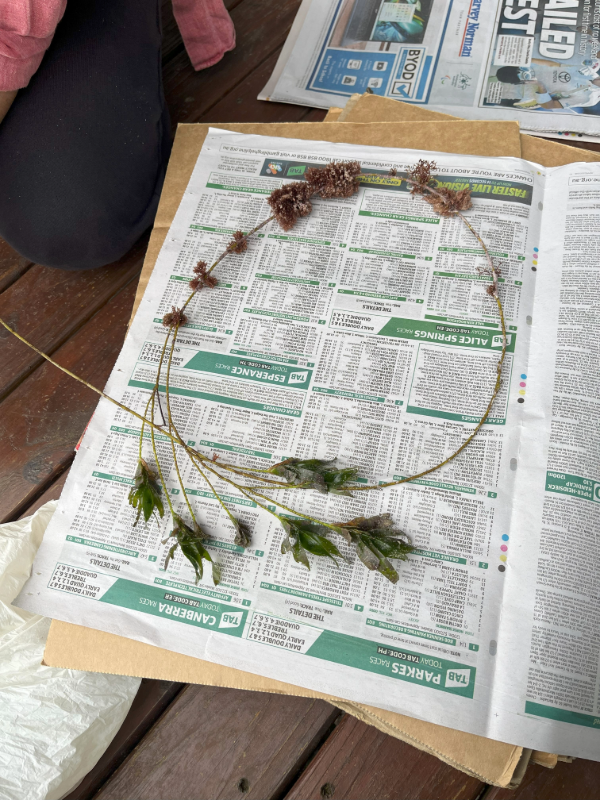

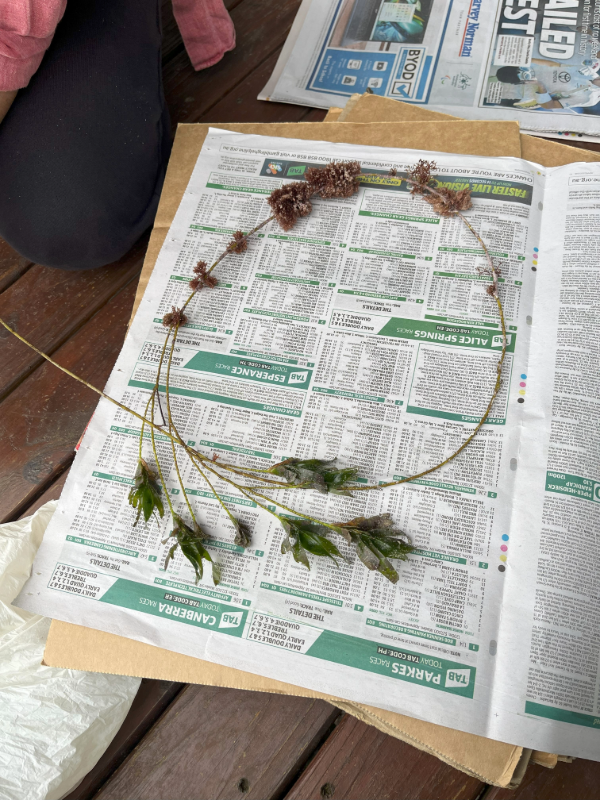

Processing a seagrass specimen back at our accommodation. Photo: Jem Barratt.

In the meantime…

Sing the praises of taxonomists to whoever you meet today and encourage them to get involved. Taxonomy is still a dwindling scientific community: we need more degrees to focus on it and more students to pursue it; more than a third of taxonomists are voluntary, being retired honoraries or passionate people doing it in their spare time. Given its importance, we need to do better.

Appreciation is a start.

Written by Herbarium staff member Jem Barratt.

The 19th of March is a day to teach (or remind) us about the crucial science of taxonomy, and to think of those that practice it.

The 19th of March is a day to teach (or remind) us about the crucial science of taxonomy, and to think of those that practice it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.