To celebrate Seaweek (4-10 Sep. 2017), State Herbarium Hon. Research Associate Bob Baldock wrote the following article for this blog…

Looking towards the west – seaweeds tell the tale of South Australia’s marine connections

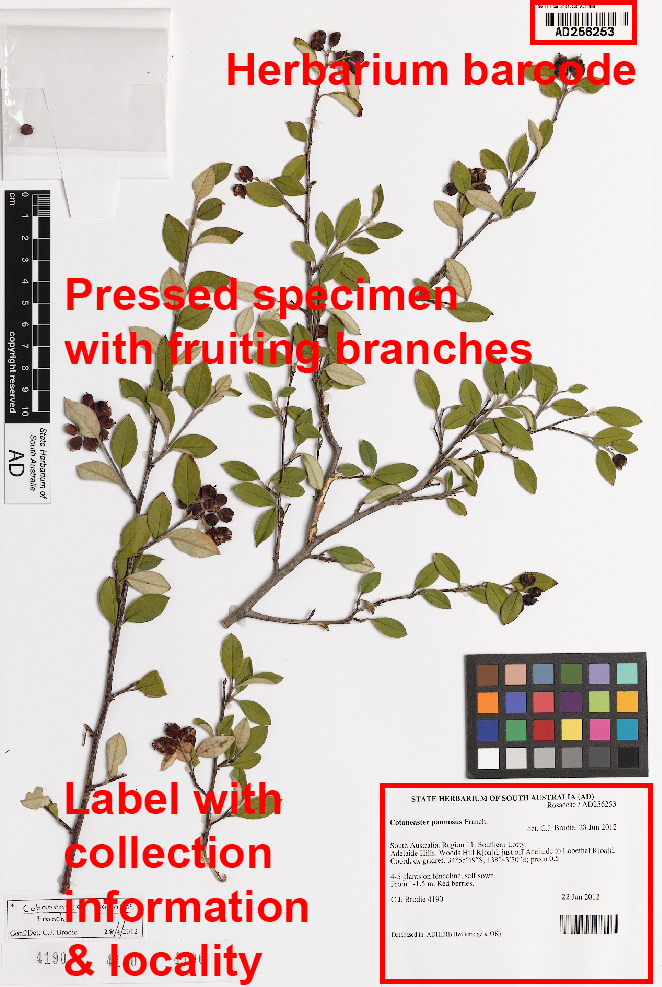

The State Herbarium houses about 90,000 specimens of seaweeds (algae), collected over some 160 years. Why so many? and why for so long?

Hypoglossum harveyanum, a rare red alga looking as if it is on fire, and even more striking under the microscope (right image). Photo: R.N. Baldock.

Well, southern Australia has more marine species belonging (that is, endemic) to our region than any other place in the world. Surprisingly, this includes the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), which, although it has more species, shares many of them with other regions. Some think we should call our region the GSR – The Great Southern Reef – just to highlight this (Bennett et al. 2015). We have some species that have only been collected a few times (such as Hypoglossum harveyanum, above). Will we ever find them again?

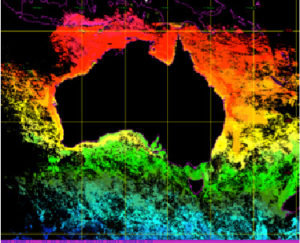

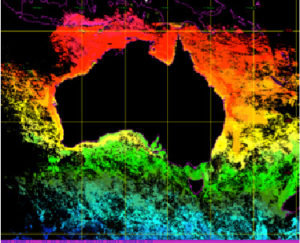

Satellite image of surface sea temperature. Source: www.cmar.csiro.au

And we also need to know if numbers, types and distributions of species are changing over time, hence the need to collect, preserve and catalogue specimens. How else will we know if climate change is affecting our coastal marine plants and animals? The vast amount of information in the Herbarium’s collections is available to answer some of these questions (Wernberg et al. 2011).

Where does southern Australian marine diversity come from?

Our continental neighbours, Africa and South America, dip further south than Australia They have a south to north distribution of marine species, related to ocean currents. But in Australia, we have a west to east warm current, the Leeuwin, that sweeps across the south of our continent. This current has peculiar swirling characteristics, seen from space that trap subtropical species and carry them as far as the SE of South Australia (Wernberg et al. 2013).

A mix of the cool water red alga Griffithsia teges and several species of green Caulerpa, a genus usually found in tropical regions, growing at Robe. Photo: R.N. Baldock.

Add to that both cold water lying in southernmost parts of southern Australia, which encourages the growth of giant brown algae, and localised upwelling of cold, nutrient rich, deep waters, due to prevailing SE winds in summer, and you have a recipe for large diversity. Odd mixtures of cool- and warm-water species can live together.

South Australian gulfs also harbour relicts from ancient sub-tropical times. One is the brown alga Cystoseira trinodis.

Occasionally drifting algae move great distances from their source. One spectacular example is the brown alga Turbinaria.

The relict brown alga Cystoseira trinodis (LEFT & MIDDLE) and a close-up of Turbinaria (RIGHT), washed into the Great Australian Bight from the Indian Ocean. Photos: R.N. Baldock.

Unfortunately, unwanted algae (“weeds”) such as Caulerpa cylindracea (Algae Revealed fact sheet under the name Caulerpa racemosa var. cylindracea; 365kb PDF) can also drift from the west, too. Recognising them from closely related species and tracing their spread along our coasts is essential for environmental management.

Caulerpa cylindracea. (LEFT) A mass of plants exposed at low tide. (RIGHT) Detail of the runner by which it spreads, and club-shaped upright parts. Photos: R.N. Blaldock.

Herbaria with their data, validated by specimens, are storehouses of information and can assist in this.

If you want to know more about the southern marine algae, have a look at Bob Baldock’s illustrated Algae Revealed fact sheets. They can be accessed by clicking the MORE button in the eFloraSA Census search, or through the static index page.

You can also check H.B.S. Womersley‘s monumental Marine Benthic Flora of Southern Australia. Species fact sheets on all southern Australian algae can also be accessed through the eFloraSA Census search, by clicking on the name of the genus or species, or by accessing the static index page.

PDFs of the scanned six volumes of the Marine Benthic Flora are available on EnviroDataSA:

- Part I – Introduction, seagrasses, green algae (21.2mb PDF)

- Part II – Brown algae (31mb PDF)

- Part IIIA – Red algae: Bangiophyceae & Florideophyceae (36.6mb PDF)

- Part IIIB – Red algae: Gracilariales, Rhodymeniales, Corallinales & Bonnemaisoniales (29.3mb PDF)

- Part IIIC – Red algae: Ceramiales 1 (36.3mb PDF)

- Part IIID – Red algae: Ceramiales 2 (40.3mb PDF).

Hardcopy volumes are still available and for sale, please contact stateherbsa@sa.gov.au for more details.

At this year’s Annual General Meeting of WMSSA, Chris Brodie was voted in as Secretary of the Society. This is a great opportunity for the Herbarium to involve itself in the wider weeds community in South Australia, and it is with enthusiasm that Chris assumes this role in the Society.

At this year’s Annual General Meeting of WMSSA, Chris Brodie was voted in as Secretary of the Society. This is a great opportunity for the Herbarium to involve itself in the wider weeds community in South Australia, and it is with enthusiasm that Chris assumes this role in the Society.

You must be logged in to post a comment.