The State Herbarium of South Australia has the largest and most varied collection of specimens of the algae tribe Polysiphonieae in all of Australia, largely due to the detailed work of H.B.S. Womersley and his encyclopaedic work The Marine Benthic Flora of Southern Australia (1984–2003).

Tolypiocladia glomerulata, a widespread species, also found in Australia (WA, NT, Qld). Photo: Moorea Biocode, French Polynesia (EOL), CC-BY-NC-SA.

This week, Dr Yola Metti from the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney is visiting the State Herbarium to study the valuable specimens housed here. Specifically, Dr Metti will look at the morphological differences within and between the genera of the tribe Polysiphonieae, as well as detailed distributions of each species.

In 2016, Yola received a 3-year postdoctoral grant from the Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS). She and her collaborators, from S Korea, USA, PERTH, MELU and NSW, will be working on the systematics of the tribe Polysiphonieae (Rhodomelaceae, Rhodophyta) of Australia in both marine and non-marine environments. This project will determine species and genus-level taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships within the tribe Polysiphonieae (Rhodomelaceae, Rhodophyta) within Australia, including both marine and nonmarine taxa. It will result in the first detailed, taxonomic study of an extremely diverse and difficult group in Australia.

In 2016, Yola received a 3-year postdoctoral grant from the Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS). She and her collaborators, from S Korea, USA, PERTH, MELU and NSW, will be working on the systematics of the tribe Polysiphonieae (Rhodomelaceae, Rhodophyta) of Australia in both marine and non-marine environments. This project will determine species and genus-level taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships within the tribe Polysiphonieae (Rhodomelaceae, Rhodophyta) within Australia, including both marine and nonmarine taxa. It will result in the first detailed, taxonomic study of an extremely diverse and difficult group in Australia.

The tribe Polysiphonieae is a cosmopolitan red algae and contains 15 genera and over 300 species; 11 genera encompassing 81 species are recorded for Australia, though there would appear to be several dozen undescribed taxa. The tribe in Australia has many problematic species, and there is a great deal of uncertainty in the application of names and distribution of taxa. Morphological characters are conflicting and highly variable, making identifications through molecular markers critical. Worldwide studies indicate that the larger genera are polyphyletic, prompting revision of the group outside Australia and resulting in new genera. The group has poorly defined genera and many of the Australian endemic genera are not represented in published analyses.

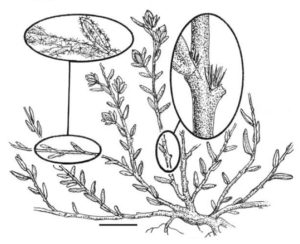

Echinothamnion hystrix. found in Australia (WA, SA, Vic., Tas.) and New Zealand. Photo: J. Huisman, Esperance, Western Australia (Algaebase).

In addition to the taxonomic issues mentioned above, the relationships between marine and non-marine taxa are uncertain: we don’t even know if they are the same species? Polysiphonieae are an important component of waterways and are used as eutrophication indicators. They are fouling organisms that can become invasive and damaging to the environment, fisheries and tourism. In Australia, the group is rarely targeted for taxonomic study, but is often collected by workers surveying aquatic habitats.

No global study of the tribe has been completed, though large amounts of data are available. Bringing together this data is required to understand the taxonomy of the group. This Australian-wide study, that will incorporate the high diversity found here along with the world-wide available data, will be key to the understanding of the tribe.

Contributed by Yola Metti, Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney

You must be logged in to post a comment.