Lengthening days, bursts of warmer weather – it must be spring. And with it, flower buds of terrestrial plants that have been surreptitiously developing over winter may suddenly burst into a great show of reproductive activity. But also, perhaps not as obvious, and often poorly appreciated, is the frantic activity in freshwater creeks, ponds and water storages in preparation for the drought of coming summer.

We are fortunate in the State Herbarium of South Australia that we have enthusiastic volunteers who not only help greatly in the day-to-day activities of the herbarium, but keep an eye on changing natural events and bring in plants that appear unusual or noteworthy. Recently one of our volunteers brought a sample of green “slime” for us to investigate. It was wrapped around the minute roots of some floating duckweed blown to the edge of a nearby city park pond.

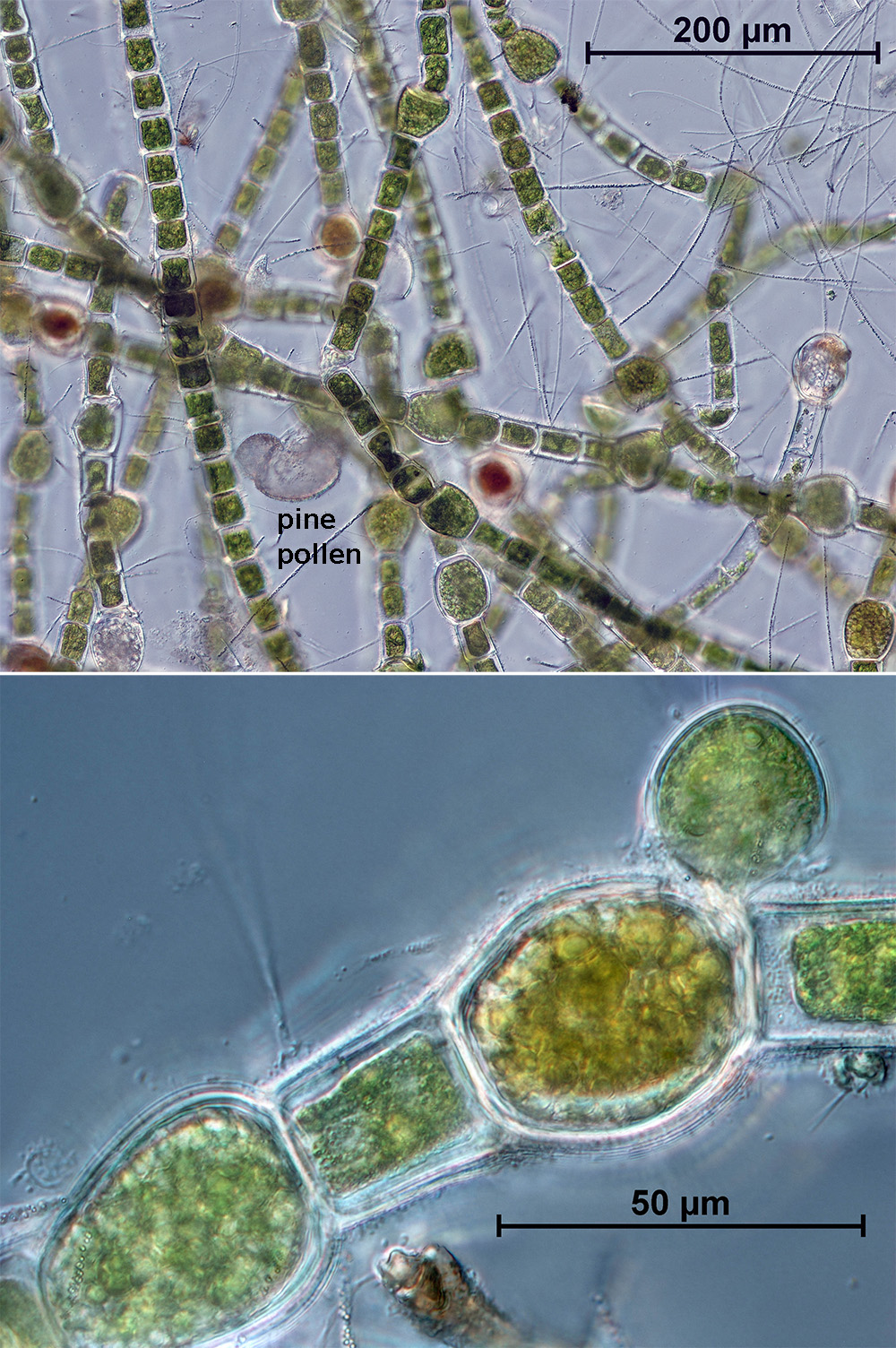

Under the microscope a whole ecosystem of plants and animals was revealed – something more remarkable than the term “slime” implies. The basis of this ecosystem was a striking green alga – Oedogonium. This had strange swellings, some green, some reddish, along the lines of green cells that make up the unbranched threads or filaments of its plant body or thallus.

Interspersed among the filaments were pine pollen grains that had dropped into the pond. These looked like Mickey Mouse hats, hence they were easily identifiable. There were also many colourless, single-celled animals going about their business, mainly filtering out single-celled algae or other animals smaller than themselves.

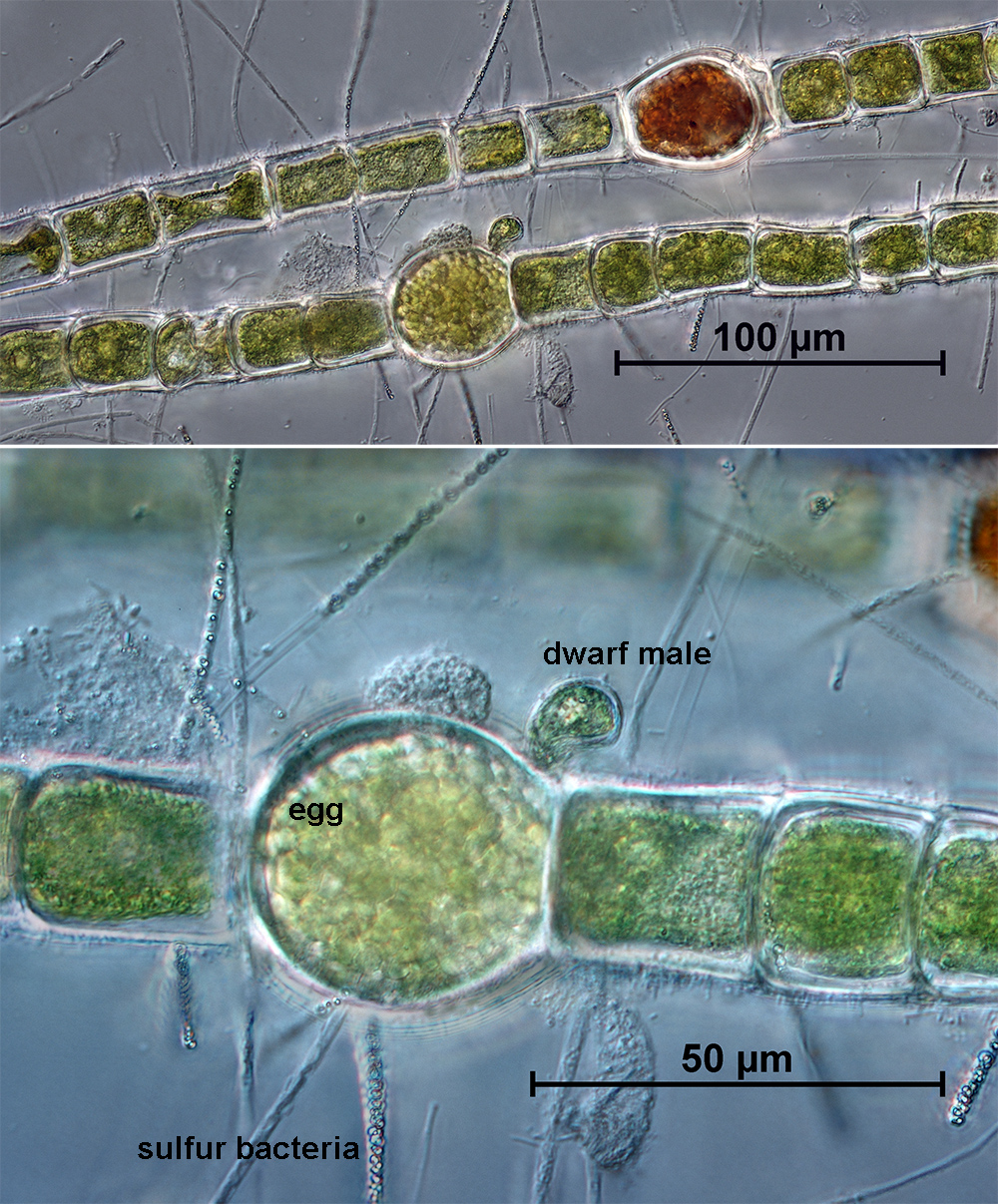

The filaments also acted as the base for minute threads of innocuous, colourless sulfur-bacteria less than 1 millionth of a metre (1 μm) in diameter. These could be identified, because they contained minute droplets of sulfur that caught the light brilliantly under the highest magnification of our microscopes.

Excitingly, the Oedogonium was reproducing. Swollen cells were acting as eggs (oogonia), and some had tiny attachments – dwarf “males” (or antheridia) – that were fertilizing the oogonia (males can be produced by neighbouring filaments or the same filament). Following fertilisation, red-brown, tough-walled zygotes had formed, ready to germinate into a new filament if conditions were right, or to sit dormant in the dried mud of waterways until the coming rains next season.

Oedogonium algae filaments with sulfur bacteria, oogonium (egg) and antheridium (male). Photos: B. Baldock.

It’s a pity that algal growth in our waterways such as that described above is denigrated. We are conditioned into thinking water bodies should be clear and blue, a state generally signalling they are sterile and lack vibrant, living ecosystems.

And, we rightly fear the appearance of the grey-green scum of toxic, blue-green “algae” that may form in waterways towards the end of summer. But, to be correct, “blue-greens” are bacteria, not true algae. This bacterium blooms at the boundary between an upper, warm, brightly lit layer and a nutrient-rich, cooler bottom layer that forms in still, non-flowing bodies of water. In cities, the nutrients generally come from wastewater run-off, including garden fertilizer and domestic pet excrement.

As a response to blooms of organisms in freshwater we seasonally often add our own toxins such as copper salts and hydrogen peroxide to kill them, wrecking benign living aquatic communities that may have helped in past times to obviate the threat of these blue-greens, by denying them excessive nutrients and establishing broader and more stable food-pyramids.

I hope you agree with me that green ”slime” can be more interesting than its name suggests. And perhaps you might appreciate it, understand its complexities and learn to live with it rather than try to obliterate it.

Further information

- Entwisle, T.J., Sonneman, J.A. & Lewis, S.L. (1997). Freshwater algae in Australia. (Sydney : Sainty & Associates). – The book is being converted to a website, part of which is already available online.

- CSIRO (2021). What are blue-green algae. [accessed: September 6, 2021].

Written by Hon. Research Associate Bob Baldock.